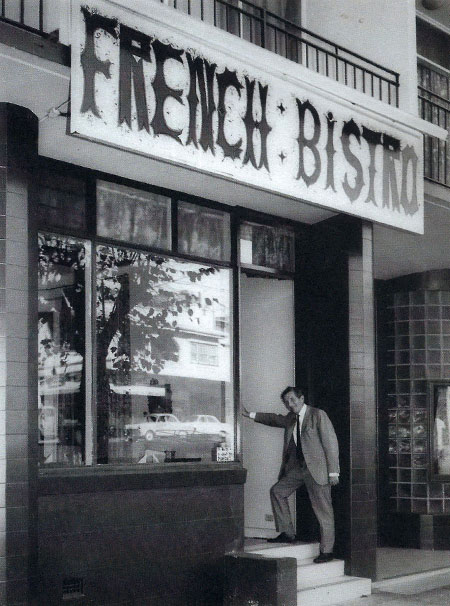

If Mirka had led the move to Melbourne, it was Georges’ idea to settle in St Kilda. The Tolarno Bistro and Hotel were ambitious projects for Mirka and Georges, almost too much so, making it a risky financial enterprise. Neither had skill in running a hotel, and extensive renovations had to take place before the restaurant opened in 1964. A further eighteen months went by before the family moved in. The Moras had bought the hotel from St Kilda residents Bill Roth and his wife Renee who had managed the hotel and the large downstairs dining room. Philippe had been joined by brothers William and Tiriel. All had separate rooms. Breakfast and dinner were taken in the bistro at ‘the family table’ and the boys grew up with a refined taste in food. The Moras brought a new sense of style to St Kilda, together with their celebrity clientele, and became well known local identities.

IF MIRKA HAD LED THE MOVE to Melbourne, it was Georges’ idea to settle in St Kilda. The Tolarno Bistro and Hotel were ambitious projects for Mirka and Georges, almost too much so, making it a risky financial enterprise. Neither had skill in running a hotel, and extensive renovations had to take place before the restaurant opened in 1964. A further eighteen months went by before the family moved in. The Moras had bought the hotel from St Kilda residents Bill Roth and his wife Renee who had managed the hotel and the large downstairs dining room. (19) Philippe had been joined by brothers William and Tiriel. All had separate rooms. Breakfast and dinner were taken in the bistro at ‘the family table’ and the boys grew up with a refined taste in food. The Moras brought a new sense of style to St Kilda, together with their celebrity clientele, and became well known local identities.

St Kilda had long been the sleazy side of town. Over the years, many of the grand nineteenth-century homes had become shabby boarding houses. Since World War II, it had also been associated with prostitution and, later, with drugs, poverty and homelessness. But it was also a vibrant community for Jewish people. While the Tolarno is in Fitzroy Street, nearby Acland Street with its cake shops, Scheherazade cafe and European style restaurants, made it a popular meeting place. Conversations in Yiddish, Russian and Polish floated in the air.

As Judith Buckrich notes, ‘From the 1960s and lasting into the 1990s, Acland Street was the centre of Jewish social life...Many Jews came straight off the boats, and many who had been living in Carlton before the war descended on St Kilda, Elwood and Caulfield, and gathered...in Acland Street’. (20)

Hungarian-born George Biron recalls, ‘the cosmopolitan atmosphere of this village of emigrés made the huge cultural shock easier for my parents. St Kilda provided true asylum’. Biron attended Brighton Road primary school, as had Sidney Nolan, one of ‘a gang of immigrant urchins’. (21) Today St Kilda is home to the Jewish Museum of Australia and, in nearby Elsternwick, the Jewish Holocaust Centre.

St Kilda was also, as I recall from the 1950s, one of the few places in Melbourne where shops were open on Sunday. It seemed quite glamorous, in a seedy way. St Kilda was also Melbourne’s playground: there was the beach in summer, as well as Luna Park and St Moritz ice-skating rink. The Palais Theatre had live performances including the Rolling Stones, Johnny Ray and Bob Hope, as well as movies. It was also home to the Melbourne Film Festival.

When I began attending the festival as a keen, teenage film-goer, I observed the large numbers of ‘older’ European people in the audience. (Everyone looks old when you’re sixteen!) They were the Jewish contingent, hungry for cinema culture in their Australian home. I remember their subtle expressions and elegant attire, conveying a sense of their own community. Mirka may have relished Melbourne but, unless you belonged to an avant-garde fraternity such as hers, it could be a dreary place in the 60s.

St Kilda was dangerous. Sex workers plied their trade in Grey Street. Drug related deaths and violence were not uncommon. The Gatwick Hotel, across the road from Tolarno, was notorious, even in the Moras’ day.

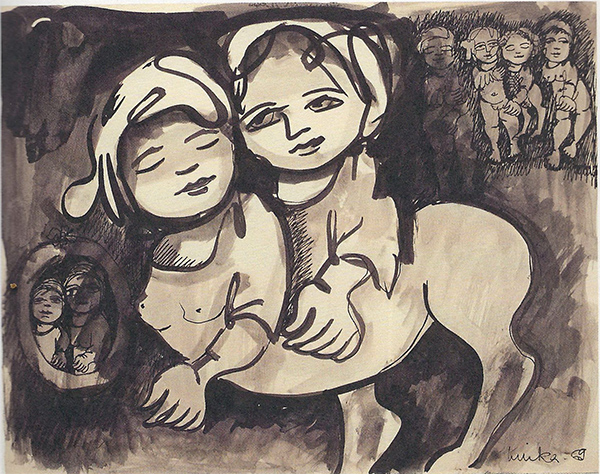

Mirka was fascinated by her new home, and sought to discover its history. ‘I love the Victorian era in Melbourne. The growth of a city and its people’. (22) But first, she wanted to decorate the restaurant. ‘I wanted to paint all the walls, like good painters do when they see walls’. (23) Soon, grand and lovely murals graced the main dining room. On the rear wall, in colours of golden-bronze, warm red and rich green float an angel, two sweet-faced children, a bird and a snake, a work which remains in situ. The figures are staples of Mirka’s iconography and were inspired by her encyclopaedic reading of myth, fairy-tales and symbolism. The mural indicates Mirka’s growing confidence – an aptitude for scale, sensitivity for colour, command of form, technical prowess and a flamboyant decorative sense. She also had a showcase for her work - Tolarno’s appreciative customers.

Mirka was slowly building her reputation. Her 1967 exhibition at Tolarno Gallery was well-reviewed. At 35, she was a serious, mid-career artist who was appreciated by a small circle of peers and patrons. It was a hectic life balancing the demands of raising her three sons and helping to manage the bistro.

Mirka’s influences in the Melbourne art world were numerous and prominent. Joy Hester, Albert Tucker, John Perceval and Arthur Boyd had been exploring the image of the large-eyed, vulnerable, often skeletally thin child since the 1940s. That image became even more emphatic in the 1950s in the hands of younger artists Charles Blackman, Laurence Hope and Sydney-based painter Robert Dickerson. Not only did Mirka know these artists, she had the opportunity to view their work in the intimate setting of Heide, Sunday and John’s home. It is impossible to consider Mirka’s work without addressing that inspiring context.

But what Mirka brought to the subject was visceral – she had seen and experienced the Holocaust. Her experiences at Pithiviers and Beaune-la-Ronde, as well as the Jewish orphanage in Brittany, were etched on her mind’s eye. These stark impressions emerged pictorially as both a testament to her feelings for the children of the Holocaust underscored by her sensitive absorption of the rich influences her artistic community offered. She was – emotionally and aesthetically – attuned to her Melbourne milieu. It was an encouraging environment for the budding artist.

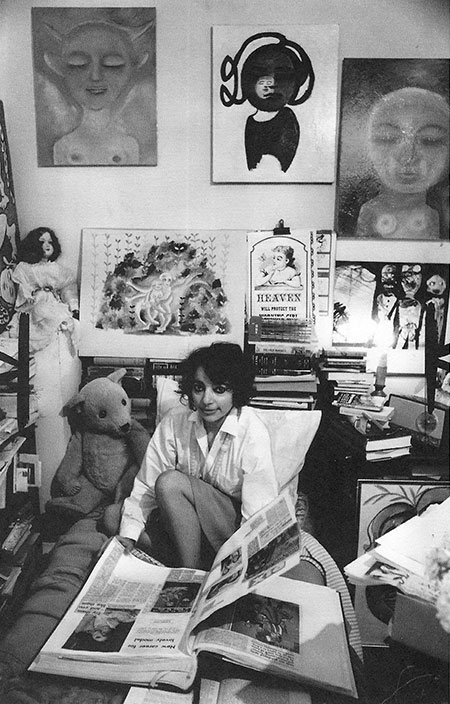

At the Tolarno, Mirka had her first proper studio, defining a zone of creative autonomy. In the basement, its windows facing West Beach Road, the studio ‘smelt like a Bendigo mine, two hundred metres down in the earth’ but Mirka relished it. (24) There’s an arresting photograph of her taken around 1968. Behind Mirka stand two, large, dramatic black and white paintings where snakes, angels and children cavort. They seem to be growing from her head like fabulous flowers in a marvellous garden, imaging her creativity. Assertively Mirka faces the camera, determined and self-possessed.

Mirka was keen to research the Tolarno’s story but was frustrated by a lack of facts. Then the poet Judith Wright told her about the Tolarno cattle station in NSW’s Riverina district, where her husband had worked as a jackaroo. Its wealthy owners were thought to have built the Tolarno. Richard Peterson queries the connection. He points out that the Tolarno was built in 1884 and went through a series of owners before it was named in 1899. (25) In around 1910 it was converted to a guesthouse with a croquet lawn at the front, the site later occupied by the bistro and upstairs apartments. (26)

Opposite the Tolarno, Mirka found a site which she believed was the former French consulate. In 1968, the impressive Victorian building, known as Voltaire-Racine, was being demolished to make way for apartments. Mirka researched it, with the help of a librarian friend, and discovered an intriguing and scandalous tale. When the first French consul to Melbourne, Count Lionel de Chabrillan, brought his bride here in 1854, she had just published her memoirs. Élisabeth-Céleste Vénard had been a courtesan. ‘In those days’, Mirka commented, ‘prostitution was a profession of distinction’. (27)

However, colonial society thought differently and, initially, Céleste was treated as a pariah. Even though attitudes towards her softened, in part due to Lionel’s impressive diplomatic skills and hard work, the couple had a wretched time. They encountered financial difficulties and illness, and, in 1858, Céleste returned to France to raise money to cover their debts. While she acquitted her task successfully, shortly afterwards, Lionel died. Little wonder Céleste titled her Australian memoir Un Deuil au Bout du Monde (1877), Death at the End of World. (28) It’s an account so bleak, her description of colonial life as so brutish and chaotic that it reads like a bizarre black comedy. Goldrush Melbourne was certainly not for the faint-hearted.

But Mirka was mistaken. While Lionel and Céleste did indeed live ‘near a village called Saint-Kilda’, precisely where remains a mystery. (29) Certainly not in the grand building that was being razed in 1968. Céleste describes their modest wooden ‘chalet’ – a kit home which she bought in France and had assembled here – as being in ‘the heart of the woods’. (30) Close to St Kilda beach – where Céleste went bathing - the house offered commanding views of Port Phillip Bay, and all the way across to Richmond and the city.

Meanwhile, Lionel ran the consulate from a number of city venues, mainly in and around Collins Street. After Lionel’s death, back in Paris, Celeste embarked, against the odds, on a prolific literary and stage career. Mirka knew Céleste’s popular novel, Les Voleurs d’Or (The Gold Thieves) (1857) set in the Ballarat goldfields.

Not only did the ill-fated love story of Lionel and Céleste pique Mirka’s curiosity but it was another Paris-Melbourne connection. Céleste was a highly creative, daring and tenacious woman, a character after Mirka’s own heart, while Antoine Fauchery was a close friend of Lionel’s. Fauchery had photographed Lionel – he looked a dashing and humorous fellow - and he was at the count’s bedside when he died. Fauchery wrote a touching letter to Céleste, giving her the unhappy details of Lionel’s demise. (31)

Mirka and Georges permitted one another to have affairs, a very French arrangement. But while Georges seemed to conduct his amours diplomatically, such restraint did not sit well with Mirka. Romantic and idealistic, she fell in love. She wrote to Sunday Reed

Dear Sunday this is a secret letter. I have fallen in love again - and this time I feel in great danger.

I will have to use my brain to the utmost. (32)

Mirka was introduced to G.R.Lansell by Sweeney Reed over dinner at Tolarno. (33) It wasn’t love at first sight. Ross recalls Mirka was ‘reluctant’ to meet him. (34) Mirka had already had several turbulent affairs. Allan Wynn was a cardiologist involved in the contemporary art scene. He was married to Sally Gilmour, an English ballet dancer. Wynn was smitten and wanted to marry Mirka. With impressive sang-froid Georges responded, ‘Mirka must chose’. Mirka considered, ‘As I already had one husband I could not see the point of having another one’. (35)

In the mid 1950s, Mirka met artist Donald Laycock. Mirka loved ‘the presence of the man. He understood paint and I could learn from him and develop my work’. (36) At the time, Laycock was a successful artist exhibiting with Violet Dulieu’s South Yarra Galleries. In Bernard Smith’s landmark book, Australian Painting, he writes, that Laycock was ‘if not the first, certainly one of the first among local artists to develop a coherent personal style from the abstract expressionist mode of invention’. (37)

The cosmic and spiritual quality of Laycock’s lushly painted works intrigued me, reminding me of Mark Rothko. In 1975, I published an essay on Laycock in Art and Australia. (38) I recall Don as a placid, self-contained man who lived in an ample, two storey Victorian terrace in Fitzroy. Mirka and I discussed Don, giving me an insight into the curious emotional politics of the affair. Going to visit Don, Mirka had ‘a vision’ which revealed him in bed with another woman. When Mirka arrived at his home she discovered her vision was indeed fact. She felt betrayed and the affair ended. Yet the resonance of the old love remained. When Mirka died in 2018, William Mora told me that one of the first to ring him with condolences was Laycock.

Ross Lansell was the bright, acerbic, young art critic for Nation (a position previously held by Robert Hughes) and fourteen years Mirka’s junior. Georges soon recognised the seriousness of the relationship and felt threatened. After three years, and unable to tolerate it any longer, Georges gave Mirka an ultimatum: leave Ross or leave him. She chose the latter: she had found her partner and there was no turning back. She did not tell Ross of her decision until she had moved from the Tolarno, taking him by surprise. (39)

It was a devastating experience for Georges and her sons. In anguish, Georges wrote to Sunday explaining why it had taken him so long to force the issue.

‘I could also, naturally, not accept that all my dreams of a beautiful old-age life together with Mirka would be shattered, Philippe – William – Tiriel torn between us, sadness in their eyes – worries for all of us, while only a few years ago we were still very close and always laughing. Naturally, Mirka’s life was awful too. She had lost all contact with me, she hated to be seen with me, or to go to see something with me together. [Cinemas, Theatre or anything]. To be with us, was for her a kind of prison, to stay at The Tolarno, to have dinner with us, was a great favour she did me. She was totally insensitive [I hope] to my position or feelings, she believed me to be like a monster. Why I don’t hate her, I can’t understand’. (40)

Break-ups are usually messy. The Moras was especially so. In the early 1960s, in a testament to their friendship, the Reeds and the Moras had built adjacent holiday houses at Aspendale beach. Charles and Barbara Blackman, Albert Tucker, John and Mary Perceval, and many others were regular summer time guests. When a split occurs, people often take sides, choosing to remain loyal to one member of the couple. From the frank, friendly and regular correspondence between the Reeds and Mirka, it seems they chose her.

Georges continued

‘Poor Sun, you might be upset to have to listen to this. Forgive me, but to whom, I ask you, could I write such confessions. We don’t see each other anymore but I can sense, that you still feel for me as before, at least that you are aware of my existence.’ (41)

Perhaps Georges would have been comforted to read these words in Mirka’s autobiography. ‘Georges was and still is the pillar of my security, even in his grave...Nothing bad could happen to me as he always stood by me, understood everything’. (42) Mirka declared, ‘the affair with Georges never ended and lasted fifty-one years’. (43)

Though Mirka’s new life was shared with Ross, who would remain her partner until her death, the couple did not live together. But it was a nourishing relationship for Mirka, giving her the right amount of freedom and intimacy to fully explore her life as an artist and a woman. She was faithful to Ross as she had not been to Georges. Over the years, I saw Ross and Mirka regularly around town, at openings, book launches and the like, clearly enjoying one another’s company. Ross was, and remains, a very private person. As regards his career, Ross describes himself as ‘a very successful writer manqué’, or failed writer. (44)

I often saw Georges out and about in Melbourne, too. He was usually accompanied by an attractive young woman, never the same one twice. Wait staff from the Tolarno? Visitors to the gallery? There was an embarrassing moment one evening at the Melbourne Film Festival. As I edged my way into the row of seats, I saw Georges with his companion. We greeted each other. Then I saw Mirka who was frantically gesticulating to me. There was one seat separating her and Ross from Georges, and she wanted me to sit there. ‘It’s Georges!’, Mirka announced in a stage whisper. I was surprised, thinking such bohemian folk would have resolved their differences long ago.

Georges was single for many years until 1985, when he married the artist Caroline Williams. Their son, Sam, was born that year. The family lived at Aspendale (the Reed and Mora holiday homes had been re-designed to form one house) while Georges also kept a pied-a-terre at the Tolarno.

In an article in the Sunday Observer, Mirka announced she had left her family. No doubt there was gossip. Mirka had suddenly disappeared from the Tolarno where she regularly ran the restaurant and greeted diners. The Tolarno was popular with artists, actors, musicians, politicians and journalists. Everyone who was anyone – from Marcel Marceau to Andrew Peacock to Bob Dylan to Bert Newton to Mick Jagger to Jean Shrimpton - dined there. It made Mirka and Georges something of a celebrity couple. Mirka’s scrapbook, crammed with newspaper articles, attests they were a high profile duo, pop cultural icons of Melbourne society. (45)

In the article, Mirka explained that, ten years earlier, Maurice Chevalier had asked her what would she do if she had to choose between her family and her art? ‘He wanted to know if I was a true artist’. (46) She replied she would choose art.

While in 1970 the Women’s Liberation Movement was gathering momentum, Mirka already had a feminist resolve. She was a solo woman artist who was unabashedly ambitious and who had left her family to follow her career. Her work addressed issues in women’s art by collapsing hierarchies between art and craft, between the ‘high art’ of painting and the ‘low art’ of sewing and embroidery. Not that Mirka was comfortable with limited notions of feminism. ‘Women’s Lib is too unsubtle’, she declared. ‘Once a woman does that sort of thing she loses her charm. After all the women have the power’. (47)

Mirka enjoyed flirting, sometimes outrageously. She was a seductive character, aware of the impact she could have on men. She enjoyed rude jokes and salacious stories. Her public persona, which could involve pulling up her dress and wiggling her bum (much to the embarrassment of her sons) could be amusing, provocative and sometimes in bad taste. She had, after all, studied theatre prior to leaving Paris.

It took a kind of reckless courage to walk out on her marriage. But if Mirka was in love, she was also betting on her career and, rather like her radical decision to move to Melbourne, it paid off handsomely. She was surrounded by a band of determined male artists. Blackman, Perceval, Boyd and Tucker were making money hand over fist, having exhibitions in major Australian galleries, travelling to London to exhibit and buying sports cars and properties in England and Tuscany.

Mirka’s commercial success never approached theirs. It took her until 1981 to buy a home. In 1973, when Mirka started teaching art workshops at the Council for Adult Education in Melbourne’s CBD, it provided her with a small but reliable income for the next 20 years. She was quite alone as a woman artist. Joy Hester, a close friend and the only female member of the Heide Circle, had died in 1960. Other colleagues such as Erica McGilchrist and Dawn Sime, while active in the Contemporary Art Society in the 1950s, were more or less invisible by 1970. Some – like Mary Perceval and Yvonne Boyd – had talent which petered out under the pressures of marriage, children and caretaking their husbands’ careers.

Joy Hester had left her child behind. In 1947, when she fell in love with Gray Smith, while her husband Albert Tucker was in Japan, she also decided to run away from home. But Joy was ill. She had been diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease, a cancer of the lymph glands, and she had been given a short time to live. Despite the hurt and angry feelings following the break, she and Tucker concurred that the best course of action was to place Sweeney at Heide. Sunday and John already doted on him. Sunday had long wanted a child, but was unable to conceive.

Did Mirka earn opprobrium from her friends and wider circle for not being ‘a good mother’? Joy did. Mary Perceval, a close friend, distanced herself, as, it seems, did other members of the Boyd clan. After inviting Mary to her home at Hurstbridge, Joy did not hear back. It was hurtful but she had to accept that perhaps Mary ‘does not approve’. (48) Though the Mora split occurred on the cusp of the liberated Seventies, Melbourne, outside of its artistic enclaves, was a very conservative place. No doubt Mirka knew the tale of Sweeney – she would have heard it from Joy herself, as well as from Sunday and John, and perhaps also from Sweeney – whom she adored. He was ‘extremely beautiful, a wild child, very intelligent...There was a kind of aura around Sweeney’. (49)

If Mirka did receive criticism, it did not sway her resolve. Perhaps the flamboyance with which Mirka and Georges conducted their private lives made their parting seem almost inevitable to their friends.

See more of the Mirka Mora Project

Credits

{slider-ex title="Author" open="false" class="icon"}

Dr Janine Burke is an author, art historian and a local resident for thirty-five years. She is Honorary Senior Fellow, University of Melbourne and committee member, St Kilda Historical Society.

{slider-ex title="Notes" class="icon"}

{slider title="From Paris to Melbourne" open="false"}

- Albert Tucker to Sunday Reed. 31 January, 1951. John and Sunday Reed Papers, State Library of Victoria.

- Albert Tucker to John and Sunday Reed. 27 August, 1950. John and Sunday Reed Papers, State Library of Victoria.

- Mirka Mora, Wicked but Virtuous: My Life, Viking, Ringwood, 2000, p.13.

- Pithiviers station is undergoing transformation as a Holocaust museum. See Melian Solly. ‘Museum to be built at Site of Nazi Occupied France’s First Concentration Camp’, December 18, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/museum-built-site-nazi-occupied-frances-first-concentration-camp-set-open-2020-180971126/ Accessed 1 July 2019.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.15.

- Zelda Cawthorne, ‘Treasure Trove of Mirka’, 18 June, 2014. https://www.jewishnews.net.au/treasure-trove-from-mirka/35684 Accessed 2 July 2019.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.15.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.20.

- Lesley Alway and Kendrah Morgan, Mirka and Georges, A Culinary Affair, The Miegunyah Press, Heide Musuem of Modern Art, 2018, p. 21.

- For a description of the history and activities of the Oeuvre de secours aux enfants see https://www.ose-france.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Bochure-100-ans-OSE-anglais.pdf Accessed 4 January 2020.

- Georges’ heroic activities in OSE are described in Monsieur Mayonnaise (2016). Documentary film. Philippe Mora, narrator. Trevor Graham, writer and director. Trevor Graham, Ned Lander and Lisa Wang producers, Antidote Films.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.40.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.25.

- Quoted in Dianne Reilly, ‘Antoine Fauchery, 1823–1861 Photographer and Journalist Par Excellence’, La Trobe Journal, no 33, April 1984, p.3, fn 9. http://www3.slv.vic.gov.au/latrobejournal/issue/latrobe-33/t1-g-t1.html. Accessed 3 July 2019. While following cash and adventure to Japan, Fauchery died in Yokohama in 1861, due to complications from dysentery. He was 37.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.159.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.48.

{slider title="Paris End of Collins Street - 1950s"}

- G.R. Lansell, Email to the author, 15 June 2019.

- In 1992, Mirka travelled to France to teach a workshop titled Adventure in Art: Mirka en Provence which included a stint at Saint-Paul-de-Vence on the French Riviera. Organised by John and Shirley Traynor, it took place shortly after Georges died. The group spent time in Paris, Mirka noting, ‘of course [the tour] included almost all the places I had been with my husband’. Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.219. In 1994, Mirka travelled to France when Philippe Mora, based in Los Angeles, invited her to attend the Cannes film festival with him.

{slider title="St Kilda, Fitzroy Street (Tolarno) 1966-1970"}

- Jackie Somerville. Telephone interview with the author. 22 May 2020.

- Judith Buckrich, Acland Street, The Grand Lady of St Kilda, Australian Teachers of Media, St Kilda, 2017, p. 110.

- Buckrich, Acland Street, p.101.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p. 85.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.87. The original 1966 mural is in the collection of Heide Museum of Modern Art.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.86. The room which Mirka first occupied on the ground floor as her studio was appropriated by Georges for Tolarno Gallery, so Mirka moved into the basement where she had three rooms. On the first floor, she had a bedroom separate from Georges which also served as a smaller studio.

- Richard Peterson, ‘Tolarno Hotel’, in A Place of Sensuous Resort. St Kilda Buildings and Their People, Chapter 17, p.5. http://www.richardpeterson.com.au/a-place-of-sensuous-resort. Accessed 4 July 2019.

- For an overview of the history of the Tolarno from its building to the 1970s see Peterson, A Place of Sensuous Resort. Chapter 17, pp.5-8. http://www.richardpeterson.com.au/a-place-of-sensuous-resort.

- Tricia Goodwin, ‘Love Among the Ruins’, The Herald, 28 November, 1968, p.21.

- It’s unlikely Mirka read Death at the End of the World available in the original French edition. If she had, she would have known that Lionel and Céleste’s home was a five room ‘chalet...made of pine with a galvanised-iron roof’ in St Kilda. Patricia Clancy and Jeanne Allen, Introduction and translation, The French Consul’s Wife, Memoirs of Céleste de Chabrillan in Gold-rush Australia, The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 1998, p.113.

- ‘We have found some land two leagues (around 10 kilometres) from the town in the heart of the woods, near a village called Saint-Kilda (sic). We are going to erect the house that I bought in Bordeaux on this site’. Clancy and Allen, The French Consul’s Wife, p.95.

- Clancy and Allen, The French Consul’s Wife, p.95.

- Fauchery’s letter, dated 4 February 1859, is quoted in full in Clancy and Allen, The French Consul’s Wife, pp.237-242.

- Mirka Mora to Sunday Reed. 10 March 1967. John and Sunday Reed Papers, State Library of Victoria. MS 13186. 2.20. Mirka Mora Correspondence.

- Sweeney Reed (1945-1979) was the adopted son of John and Sunday Reed. Sweeney was the son of the marriage of Joy Hester and Albert Tucker. In 1967, Sweeney was director of Strines, a gallery in Carlton.

- G.R. Lansell. Email to the author, 16 December 2019.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, pp. 165-166.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.169.

- Bernard Smith, Australian Painting, Oxford University Press, London, 1971, p. 312.

- Janine Burke ‘Donald Laycock’, Art and Australia, October – December 1975, Vol 13, No 2, pp. 144-151.

- G.R. Lansell. Email to the author, 16 December 2019.

- Georges Mora to Sunday Reed. 27 December 1970. John and Sunday Reed Papers, State Library of Victoria. MS 13186, Box 2/18, File 7.

- Mora to Reed. 27 December 1970. John and Sunday Reed Papers, State Library of Victoria. MS 13186, Box 2/18, File 7.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, pp.166-167.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.163.

- G.R. Lansell. Email to the author, 16 December 2019.

- Mora’s scrapbook is in the collection of Heide Museum of Modern Art.

- Sheila Sibley, ‘And art was her choice’, Sunday Observer, 21 June, 1970. Interestingly, Mirka included the same anecdote in her autobiography Wicked but Virtuous: My Life (2000) indicating the potency of Chevalier’s question and her answer. See Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.77.

- Keith Dunstan, ‘A Place in the Sun’, The Sun, 4 June 1971.

- Janine Burke (ed), Dear Sun: the letters of Joy Hester and Sunday Reed, William Heinemann Australia, Melbourne 1995, p.203.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.54.

{slider title="St Kilda, Wellington Street 1970-1975"}

- The shopfront-dwelling at 26 Wellington Street was demolished to make way for a block of units.

- Sheila Sibley, ‘And art was her choice’, Sunday Observer, June 21, 1970.

- Sheila Sibley, ‘And art was her choice’, Sunday Observer, June 21, 1970.

- Janine Burke and Lynne Cook, ‘Mirka Mora’, Farrago, April 26, 1974, p.11.

- Transcript of interview with Mirka Mora by Barrett Reid, 14 January 1971, p.21. Barrett Reid Papers, State Library of Victoria. MS 13339, Box 9, File 2, Wallet 1/1.

- Sabine Cotte, Mirka Mora: A life making art, Thames and Hudson, Melbourne, 2019, p. 80.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.156.

- Jane Freeman, ‘Mora’s magic in full bloom’, Sydney Morning Herald, 6 September, 1996, p.14.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, pp. 147-148.

- Burke and Cook, ‘Mirka Mora’, Farrago, p.11.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p. 148.

- Jenny Kee with Samantha Trenoweth, A Big Life, Lantern, Melbourne, p.132.

{slider title="St Kilda, Barkly Street 1981-1999 and beyond"}

- Mirka Mora to Janine Burke, 2 November 1981. Mirka Mora Papers. Box 3, Correspondence. Brown Envelope 11. Heide Museum of Modern Art.

- William Mora. Telephone conversation with the author. 6 November 2019.

- Mora to Burke, 2 November 1981. Mirka Mora Papers, Box 3, Correspondence. Brown Envelope 11. Heide Museum of Modern Art.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, pp.53-54.

- Bridie Carter. Email to the author. April 16, 2019.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.299.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.300.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.300.

- Rachel Berger, ‘Memories of Mirka’, St Kilda News, Issue 81, October-November 2018, p. 21.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p. 149.

- Helen Halliday, ‘Memories of Mirka’, St Kilda News, Issue 81, October-November 2018, p.19.

- Halliday, ‘Memories of Mirka’, St Kilda News, p.19.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p. 152.

- Ann Holt, ‘Memories of Mirka’, St Kilda News, Issue 81, October-November 2018, p.16.

- Gail Donovan, ‘Memories of Mirka’, St Kilda News, Issue 81, October-November 2018, p.18.

- Donovan, ‘Memories of Mirka’, St Kilda News, p.18.

- Ross Lansell remembers it rather differently. ‘Gail and Kevin very generously provided us two with a late impromptu Christmas lunch for free (also from memory, not exactly for the first time). I remember shortly thereafter personally delivering to Gail and Kevin (Mirka wasn’t present) a modest gouache...to thank them’. G.R.Lansell. Email to the author. October 31, 2019.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.242.

- Cotte, Mirka Mora: A life making art, p.177. Cotte was also responsible for the conservation of Mora’s Flinders Street Station mosaic. She worked on it in March 2009, then again in November 2010.

- Cotte, Mirka Mora: A life making art, p.177.

- Cotte, Mirka Mora: A life making art, p.177.

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, p.243.

- Tolarno Gallery is now at Level 4, 101 Exhibition Street, Melbourne (at time of writing) and its director is Jan Minchin who joined Georges as assistant director in the late 1970s.

- Guy Grossi, ‘Memories of Mirka’, St Kilda News, Issue 81, October-November 2018, p.18.

- G.R.Lansell. Email to the author. 16 December 2019.

- Serge Thomann. Email to the author. 6 November 2019.

- Serge Thomann. Email to the author. 6 November 2019.

- Jane Touzeau. Email to the author. 5 January 2020.

{slider title="Epilogue"}

- Mora, Wicked but Virtuous, pp. 299-302.

{/sliders-ex}

{/sliders}