Introduction

In introducing this study of the history of places of worship in St Kilda it must be recognised that for many tens of thousands of years before white settlement there was a rich spiritual life among the indigenous people. The Melbourne area was originally inhabited by the people of the Kulin Nation. It was divided into a number of language groups, one of which, the Bunurong, inhabited the Mornington Peninsula, the catchment area of Westernport Bay and the coastal strip of Port Phillip Bay as far as the Werribee River. The area encompassing modern-day St Kilda was the estate of traditional owners from one of the six Bunurong clans, the Yalukit-willam.[1]

The land has profound totemic or religious significance for Aboriginal people. In the ‘dreamtime’ creative beings, neither human or animal but with attributes of both, formed the physical features of the land and the flora and fauna, including humans.[2] A Kulin story is that Bunjil, the ancestral creator, placed rocks in the area now known as St Kilda to stop the sea after it broke through the heads, thereby forming Port Phillip Bay.[3] For Aborigines the land represents the home of their ancestors and the eventual repository for their own spirits. They belong to the land and are an extension of it.

The land and the sky are dotted with sacred sites and constellations which were integral to the rhythm of Aboriginal life. Here the ‘ancestors left part of their energy ... which may be actualized in the present through rites and ceremonies to ensure that the species of creation remain abundant’.[4] Ceremonies and rituals were an important part of Aborigines’ lives, including initiation practices, which marked the transition from childhood to adulthood, and burial rites. Religion provided the law and prescribed patterns of behaviour and living. The Aboriginal Dreamtime has been formally recognised as a religion by the Council of Churches.

Regrettably, today we do not know where these sacred places were because they were not recorded. The best known site in St Kilda related to Aboriginal spirituality is the Corroboree Tree, which is believed to be the site of ceremonial activity prior to the arrival of the Europeans. It is located in Albert Park Reserve at the corner of Queen’s Road and Fitzroy Street. This red gum, currently on the register of the National Estate, is at least 300 years old and is the last survivor of the open woodland that once covered this area.[5]

Overview of churches and their role in the social and architectural history of St Kilda

Churches and synagogues are public buildings which reflect a community’s religious beliefs as well as its more earthly aspirations and concerns. These places of worship cannot be considered just in architectural terms as landmarks in the suburban landscape. In the past, churches were more than places of worship; they were the very centre of the community. Here rites of passage were formalised with baptisms, marriages and funerals. They were also meeting places and the source of authority, respectability and morality, which had a huge impact on how people lived their lives. They were dominated by the prosperous, social elite and represented the establishment and conservatism.

Churches were a focal place for social activities with youth groups, sporting events, annual Sunday school picnics, concerts and prize givings. Membership of church choirs, attending or teaching in Sunday schools, and serving on church committees was a major part of many people’s social, cultural and spiritual life. It would be interesting to know how many people met their future spouse through their church. While much of this social activity declined after World War II, some congregations in St Kilda are now actively developing programs that once more attract young people.

The church community provided financial and emotional support for members. They also extended social and welfare support and friendship to newly arrived immigrants who had left their communities and families behind. At first the churches established in St Kilda reflected the established religions of the predominantly British settlers but other religious groups established themselves in St Kilda, notably the Jewish community and post-war immigrants from Europe, including the Ukrainian members of the Autocephalic Orthodox Church. The diverse range of religious denominations established in St Kilda reflects the freedom of worship possible in Australia. Many groups had been denied such freedoms in their homelands. The persecution of the Jews in many lands is an obvious example. Generally, they have established synagogues and enjoyed religious toleration in Australia, although the Adass Israel shule (synagogue) in Glen Eira Avenue, Ripponlea, was severely damaged in an arson attack on 1 January 1995. Catholics had been oppressed in Ireland and England until Catholic Emancipation in Britain returned most of their civil liberties in 1829, while Baptists, Congregationalists and English Presbyterians had also suffered persecution.

The building of churches was an important part of the development of early white settlements in Australia. The 1836 Church Act provided for government contributions to the three major denominations: Anglicans, Roman Catholics and Presbyterians, and approved minor ones. Support was on a pound for pound basis from a minimum of £600 to a maximum of £2000. The government also paid an annual stipend of £150 to the clergy of the three denominations permanently represented in Melbourne in 1839.[6] When Victoria separated from New South Wales in 1851, the new colony consisted of 48% Anglican (Church of England), 23% Roman Catholics, 16% Presbyterians and 7% Methodists.[7]

The Church of England was the established church in England, dating from the reign of Henry VIII of England, during which the English Church separated from the Roman Catholic Church and the English sovereign, not the Pope in Rome, became the head of the church. The Church of England was also the established church in Australia and enjoyed similar prestige in Victoria in the nineteenth century where the governor and most officials belonged to it and its bishops and clergy were given precedence over the clergymen of other denominations.[8] The church later adopted the title of Anglican Church in Australia. Anglican churches were divided into High Church (or Anglo-Catholic) and Low Church. The former consider themselves as a reformed form of Roman Catholicism and All Saints’ Anglican Church in St Kilda, with its elaborate interior decoration and rich liturgical and musical life, is a good example. Low churches are more critical of Rome and ascribe to the position that the Scriptures (not the Pope) are the sole authority. This was also the position of other Protestant denominations. Presbyterianism was the dominant church in Scotland and was founded by the reformer John Calvin. The Methodist Church was founded by John Wesley in the late eighteenth century.[9]

Government surveyors designated land ‘suitable for churches’ when planning towns. The land chosen was often on high ground and imposing buildings were built to ‘look up to’ as people approached, quite often on foot. (Lack of transport, especially for the poor, is one reason why so many churches were built in relatively close proximity.) The various denominations were grouped together although on occasion a denomination requested other locations. An Act passed in 1870 provided for the cessation of state aid in 1875 and church land was converted to regular freehold titles. Previously, the land was held on condition it was used only for religious or educational purposes. This legislative change has resulted in church land being sold for commercial purposes without legal constraint, which has at times created conservation issues.[10]

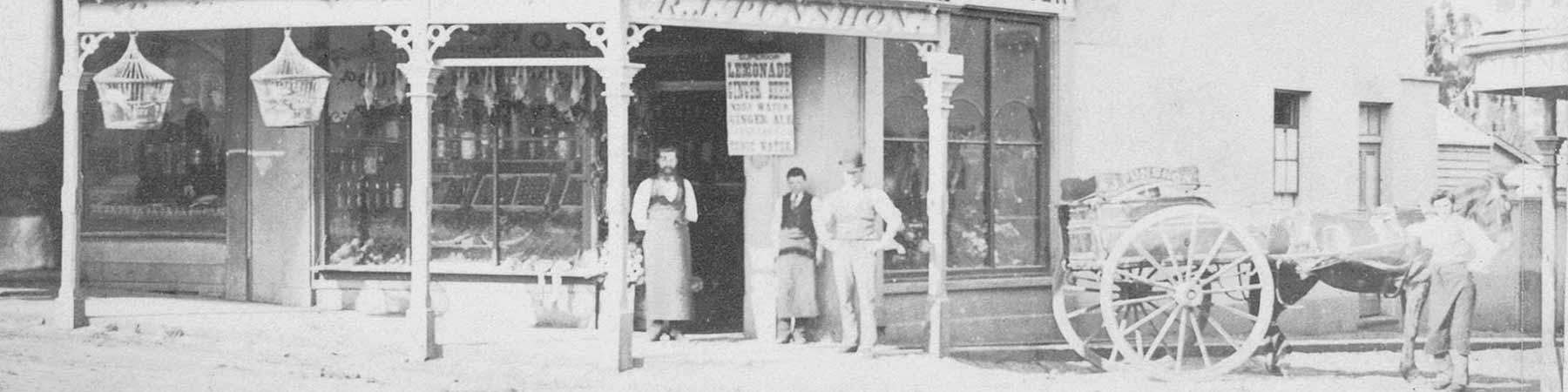

The major denominations all established themselves within St Kilda in the early years of settlement. The first Crown Land sales in St Kilda were in December 1842. Early services were typically held in private homes and as the number of worshippers grew, buildings were rented and then churches built. The first known service in St Kilda was held on 23 December 1849, the Sunday before Christmas, by an Anglican, Henry Jennings, at his home in Melbourne Terrace, now Fitzroy Street. His wife conducted the Sunday school with sixteen children in attendance that first day. The following Sunday six worshippers attended the service.[11] On 6 January 1850 the first service conducted by an ordained minister took place. The Reverend W. W. Liddiard preached to thirty people. Services were moved to the more spacious home of James Moore while building took place. A wooden building in Acland Street was used as a school and a church. It was soon replaced with a brick structure and was licensed in 7 November 1851.[12] The foundation stone for the substantial bluestone Christ Church in Acland Street, St Kilda, was laid in 1854 and it opened in 1857. It is the oldest surviving church in St Kilda. The Anglican church of All Saints’ in Chapel Street, St Kilda East, opened the following year.

Catholic services began in a modest brick building in 1853 and the foundation stone for St Mary’s in Dandenong Road, St Kilda East, was laid in 1859. The first Wesleyan Methodist service was in an iron building in 1853 and the Presbyterians commenced services two years later, also in an iron building. These buildings were dispensed with as soon as possible, with the Wesleyan Methodist church on the corner of Fitzroy and Princes Street, St Kilda, being built in 1857-58 and the Presbyterian Church on the corner of Alma Road and Barkly Street opening in 1860. This was demolished and replaced in 1885-86 by an imposing Gothic building. Situated on a prominent hilltop position, the highest point in St Kilda, its spire was a landmark for sea captains sailing up Port Phillip Bay. Its dominance of the landscape symbolises the peak of church building in St Kilda when the city was the home of the well-to-do.

The foundation stones for other churches were laid during the next thirty years: the United Free Methodist Church in Pakington Street, St Kilda, in 1859; the Free Presbyterian Church in Chapel Street, St Kilda East, in 1864; the Jewish Synagogue in Charnwood Grove, St Kilda, in 1872; the Methodist Church in Chapel Street, St Kilda, in 1877; Holy Trinity on the corner of Brighton Road and Chapel Street, St Kilda, in 1882; Sacred Heart in Grey Street, St Kilda, in 1884; and the Congregational Church on the corner of Hotham and Inkerman Streets, St Kilda East, in 1887. While most of these churches were variations of the Gothic style, St George’s Presbyterian Church, built in 1877 in Chapel Street, St Kilda, stands out for its landmark banded belltower, which is 33.5 metres tall, and the dramatic use of polychrome (multi-coloured) style.[13]

As early as the 1850s St Kilda was the ‘preferred suburb of the wealthy’[14]who sought to escape the pollution and disease of the city and who enjoyed the sea views and bracing fresh air. The churches built in the 1850s to 1880s reflect the prosperity and aspirations of their congregations, and of course, their social class. Gothic designs were traditionally preferred by Anglicans and Roman Catholics while the reformist religions tended to favour simpler buildings, avoiding the ‘Papist’ Gothic. However, in Victoria the Presbyterians, Methodists and Congregationalists also built substantial Gothic churches, reflecting their prosperity in the new colony and the competition to attract members. The Jewish community was also attracted to living in St Kilda in the 1860s and 1870s and they established a congregation and built a synagogue which was opened in 1872.

The Christian denominations and the Jewish community provided social, cultural and moral leadership in the St Kilda community. The religious leaders were educated and socially well connected in the colony. They provided leadership to the fledgling community and were active in a wide range of activities, including municipal affairs.[15] Their wives, daughters and sisters were also leaders of women’s groups such as church auxiliaries or other philanthropic organisations at a time when governments provided minimal assistance to the needy. The churches were also in the forefront of establishing day schools. It was common to erect a schoolroom first, which was also used for worship on Sundays.

The financial crashes associated with the 1890s Depression bankrupted many wealthy families. The grand homes for which St Kilda was renowned were sold and many were later converted into boarding houses. Notably the only new church built during the next two decades was the Salvation Army barracks at 17 Camden Street, St Kilda East, which were begun in 1892. In the following decades the wealthy moved to more fashionable suburbs such as South Yarra or Toorak and St Kilda’s fortunes declined. The population of Elwood was growing, however, and several churches opened there. Elwood Presbyterian Church, on the corner of Scott and Tennyson Streets, was opened in 1912. The Anglican St Bede’s in Ormond Road, Elwood, and the Baptist Church in Pakington Street, St Kilda, were both built during World War I in red brick, their simple designs reflecting wartime constraints. Similarly, the austere Our Lady of Dolours in Cowderoy Street, West St Kilda, was built during World War II. Between the wars, grander places of worship were built, with St Kilda’s Hebrew Congregation building a new synagogue in 1926-27 to replace the original one. An impressive Romanesque church named St Columba’s, in Normandy Road, Elwood, was begun in 1929.

The increased number of Jews settling in the St Kilda area before and after World War II also resulted in new congregations being established. After renting or buying places that they then outgrew, the foundation stones for their current synagogues were laid as follows: Temple Beth Israel, at 76 Alma Road, St Kilda, in 1937; Elwood Talmud Torah Congregation, at 39 Dickens Street, Elwood, in 1956; and Adass Israel Congregation at Glen Eira Avenue, Ripponlea, in 1964.

In more recent times, other immigrants settling in St Kilda have established their own churches, notably the Ukrainian Autocephalic Orthodox Church. Evangelical congregations have also established congregations in St Kilda, and many church communities now focus their ministry on assisting the poor and disavantaged, as well as those with physical or psychological problems. These developments reflect the changing patterns of religious worship in St Kilda and the wider community.

St Kilda’s changing fortunes saw it evolve from an exclusive residential suburb to a suburb renowned for prostitution, organised crime and significant poverty. In more recent times, it has emerged as a cosmopolitan, seaside suburb, albeit still with serious social concerns. The various church communities have had to confront declining attendances and make hard decisions on how to allocate decreasing resources while attempting to address the poverty and suffering in the broader community.

It is an irony that almost every church is a local landmark ‘prized by some of those who live in the area or who were former members of the congregation’.[16] Yet many such buildings are no longer needed by the present church congregation. Some churches became redundant when the Uniting Church came into being, although in St Kilda the two Presbyterian congregations chose to remain independent. Many churches represent a major investment of capital in the past and are major architectural works in the town or suburb.[17] Problems are exacerbated by the proliferation of church buildings and the high proportion of assets they (or the site) represent. Churches tend to be centrally located on generous sites tieing up valuable real estate. They also tend to be elaborate buildings with interior furnishings, objects and fabrics that present technical problems beyond the norm when it comes to maintenance, conservation and restoration. For example, it is estimated that the organ in Christ Church will cost $500,000 to re-build. Money spent restoring such buildings and their interiors and furnishings has to be diverted from other worthwhile causes, which makes for difficult decisions that are always open to criticism.[18]

Some church communities have devised creative ways of preserving their buildings. Churches and their associated buildings such as manses and halls are now being used for a wide range of activities. They lend themselves to uses such as kindergartens or school halls. St Bede’s in Elwood has a kindergarten operating from its extensive hall at the rear of the church, while the original Presbyterian church at Elwood is now used as a creche. In St Kilda, church buildings are also used as soup kitchens, housing for street kids and centres offering legal aid and assistance for the disadvantaged. The presbytery and hall at Sacred Heart, St Kilda, are primarily used by the Sacred Heart Mission, which provides a range of social services to the community. Every day about 400 people enjoy a free, three-course lunch in the hall. The former East St Kilda Congregational Church is now used as the Centre for Creative Ministries, which combines the arts with worship and community service. More unusually, the forecourt of the Holy Trinity Hall has been used as a used car showroom for many years.

Other churches have been the victims of insensitive re-development. The most glaring example in St Kilda is the former Wesleyan Church in Fitzroy Street, St Kilda. It has been surrounded by a range of commercial buildings and the integrity of the site has been destroyed. Of even greater concern is the heritage that has been lost through the demolition of churches. The Methodist Church in Elwood was demolished in the late 1960s and replaced by an electricity sub-station. The former Independent Church in Alma Road, St Kilda, was demolished in the 1990s despite being assessed as having local significance as a landmark on St Kilda Hill.[19] The places of worship in St Kilda are an important part of our heritage and as such deserve community protection and preservation.

[1] Gary Presland, Aboriginal Melbourne: The Lost Land of the Kulin People, McPhee Gribble and Penguin, Ringwood, 1994, pp. 40-41.

[2] Mudrooroo, Aboriginal Mythology, Thorsons Harper Collins, London, 1994.

[3] Meyer Eidelson, The Melbourne Dreaming: A Guide to the Aboriginal Places of Melbourne, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 1997, p. 40.

[4] Mudrooroo, Aboriginal Mythology, p. viii.

[5] Eidelson, The Melbourne Dreaming, p. 40; and Presland, Aboriginal Melbourne, p. 29.

[6] Miles Lewis, (ed.), Victorian Churches: Their Origins, Their Story & Their Architecture, National Trust of Australia (Victoria), Melbourne, 1991, p. 5.

[9] See the glossary for definitions of the various denominations.

[11] John Butler Cooper, The History of St Kilda 1840-1930, Printers, Melbourne, 1931, vol. 1, p. 323.

[13] For explanations of architectural styles see: Lewis, Victorian Churches, pp. 20-35 and information on the various denominations and their preference for particular styles of architecture see: Ibid., pp. 8-19.

[14] Eidelsen, The Melbourne Dreaming, p. 2.

[15] Timothy Hubbard, ‘The Former Independent Church, 9 Alma Road West, St Kilda: A report to the Minister for Planning and Urban Growth supporting the addition of the building to the register of classified buildings in the St Kilda planning scheme’, Timothy Hubbard Pty Ltd, South Melbourne, 1991, p. 14.

[16] Lewis, Victorian Churches, p. 3.

[19] Hubbard, ‘The Former Independent Church’, p. 9.