.David Seddon arrived in Australia in 1848 to lead the first congregation at Christ Church, Acland Street St Kilda. He came with a dark history which has been provided to the Society by a contributor from Engand who has been investigating the Rev David Seddon and exploring his history by way of court transcripts. This sordid history has been collororated by work done by Liz Kelly confirming that in in 1868 he was again suddenly forced to depart- this time for England due to further accusations of misbehaviour........

Jeffrey Stafford, the author, submitted this story from England.

Mary Green was a vulnerable, uneducated girl who began work as a drawing frame tenter in the card room of Joseph Sidbotham's factory in Broadbotton at a young age, as did most girls in the surrounding area. Mary was an active member of the Church and Sunday School. She was the illegitimate daughter of Isaac Ashton, with whom she lived.

For the third consecutive morning, nineteen-year-old Mary held her head over the stinking backyard privy and vomited. On the first morning, it had happened; Mary had blamed it on something she had eaten for supper the previous night, but Isaac Jackson, the man she lived with, had no ill effects. Mary knew she was pregnant but quickly put it to the back of her mind because she didn't want to think about it, but the truth was unavoidable. Mary endured her morning sickness for another month until, in May 1847, she told her father that she would soon be a mother and that the child's father was no other than the Rev. David Seddon, the vicar of Mottram. It was a claim that would shake this small community to the core. The news split the village; families in Mottram took sides, and few remained neutral. Thus begins the story of Mary Green and the vicar of Mottram.

Born in Burslem, Staffordshire, the Reverend David Seddon had met his future wife, Hannah Paul, while working as a missionary in Jamaica. She was another apostle born in Chinnor, Oxfordshire. Eventually, they married and returned to England, where in 1840, Seddon accepted the perpetual curacy of St Michael and All Angels Church, Mottram-in-Longdendale.

On November 30, 1847, Mary gave birth to a male child, and she made it known throughout the village that no one else but the Reverend David Seddon was the child's father.

The application for the usual affiliation order took place at Hyde Petty Sessions on Monday, January 10, 1848, before Mr J Turner of Godley, Chairman; Mr J Howard, of Brereton Hall; and Mr R Ashton, of Hyde. Mr Hudson, solicitor and coroner of Stockport, appeared for Mary Green; Mr Green, a barrister, appeared for the defendant, the Reverend David Seddon. The new courthouse in Hyde was full of spectators, clergy, surgeons, and the public.

Mr Hudson stated the case and applied for the usual order of affiliation.

He told the court that he would call several witnesses to prove that Mary Green and the Reverend Seddon had been alone at various times under suspicious circumstances, at the vicarage and in the girls' own home.

Mary Green, the mother of the child, Joseph Green, was the first witness called and was under examination for almost three hours. The newspapers described Mary as a quiet, docile, intelligent girl of twenty.

Mary then told the court that she had attended the Sunday School in Mottram since she was a young girl and had received a Bible for her excellent conduct. After describing the birth of her child, she stated quite adamantly that the Reverend Seddon of Mottram was her child's father. On Sunday before Christmas in 1846, Mrs Seddon sent her from the Sunday School to the vicarage to collect some magazines. Mr Seddon was in the vicarage at the time and went into the parlour or dining room and then went upstairs to the drawing-room or study to look for them, and he called me to come. Mary then detailed some liberties which Seddon took on that occasion. On Christmas day, I was told by James Mellor, a teacher at the Sunday School, that the vicar wanted me at the vicarage. I stood in the kitchen and waited until the vicar called me into the parlour. He told me he would give me a new 2-shilling hymn book if I returned the old one. I returned home at once, retrieved my old hymn book, and returned to the rectory. The vicar was in the parlour directing some letters for the servant to post. While I was waiting, William Harrop, the parish clerk, came with the collection from the morning service. Once he left, the vicar took up a shilling, put it into my hand, and told me that would be the same as paying for the book. Mr Seddon told me to put the collection money in my dress and take it upstairs to the drawing-room, which I did. He followed me upstairs and gave me a 2-shilling hymn book and a catechism. No one else was upstairs or in the room. Mary described a repetition of the sexual liberties he took with her. On Sunday after Christmas day, following the morning service, the vicar sent for me in the vestry and, while we were alone, asked if I had any plans for that week. I replied ‘no’. He asked on what day I washed, and I replied Wednesday. He then asked if he might come to see her father about attending church. I said I did not mind.

The next day, Monday, December 27, the vicar came to see my father while I was washing in the back kitchen. A young woman named Ann Hobson came in through the back door, so I put on my dress and went into the front room where my father and the vicar were seated. The vicar asked for the Catechism he had given me, handed it to Ann Hobson, and promised to provide me with another. The vicar and Ann Hobson left together, but he returned later in the evening between six and seven and brought me another Catechism. Still, he had not been in the house more than a few minutes when Ann Hobson returned to collect some sewing, and the vicar left shortly afterwards. The vicar came to the house one Saturday night while I was alone. It was about the time that Ebenezer Woodward died in March 1847. He followed me into the kitchen. Mary then described some sexual conduct that took place. While we were in the kitchen Ellen Holgate, a young woman, walked in, and I went with her; and the vicar picked up two potatoes from near the slopstone and followed Ellen with the potatoes in his hand and asked her how much she paid for them. She told him she did not know because her father had bought them. The vicar spoke to Ellen, and on learning her mother was ill, he left but returned ten minutes later. Ellen had already gone by then. The vicar asked if I thought Ellen had noticed them, and I said I didn't think so. He gave me a shilling and left, only to return for the third time, and while he was there, my father came in accompanied by a girl named Sarah Platt. The vicar left again soon after.

The next day, Mrs Seddon sent me from the Sunday School to the rectory to fetch a memorandum book. I stood in the lobby while the vicar went to look for it in the parlour; he told me he could not find it and went upstairs to the drawing-room, shouting for me to follow. The vicar sat me down on a chair in the drawing-room and closed the door. Mary then described how the vicar sexual interfered with her. Hearing footsteps, the vicar stopped what he was doing and opened the door. Seeing Nancy Robinson, his servant standing there, he told me he could not find the book and sent Nancy away to look for it; she brought it back to the drawing-room, and I left and took it to Mrs Seddon.

The following evening, I gave my Bible to Fanny Cooper to have my name written in it; the following Sunday, Mrs Seddon sent me to the vicarage to fetch my Bible. The vicar was not at home, but on my way back to the school, I met him near the vicarage, and he asked me to return to the vicarage with him, and he would write my name in my Bible. When we reached the vicarage, he took me upstairs to the drawing-room again. Mary then described how Seddon sexually molested her again. While we were in the drawing-room, William Harrop, the clerk, came in. The vicar then wrote my name in my Bible, and I left. On the night of Tuesday, March 16 1848, I can remember because it was the first Tuesday after short-time work had started at the factory in Broadbottom. I went with Elizabeth Holt to a lecture in Broadbottom.

I returned home by the Old Road, leaving Elizabeth Holt at the door. I had to pass the vicarage to reach home, and when walking by, I noticed the vicar on the opposite side standing at the gate. He crossed, took hold of my arm, and led me into the old building near the vicarage. I told him someone might see us, but he ignored me and took me into the building. Mary said that he had intercourse with her in the building, and while there, she told the vicar that she had had no improper intimacy with any other man, only Thomas Jackson, a servant of Dr Siebotham of Mottram. The following Tuesday, the vicar came to my father's house between seven and eight o'clock in the morning and asked me questions about my private life. I saw Nancy Simister at the door while the vicar was alone with me. The following Monday evening, a class of young girls were practising singing at the vicarage, and while I was in the kitchen, the vicar asked if I had seen a doctor. He then suggested that the father of the child I was carrying must be Thomas Jackson. I told him that was impossible. I then told my father about this when he questioned me.

Seddon's barrister cross-examined Mary Green, but he could not shake her evidence.

William Harrop, parish clerk of Mottram since 1840, was then called to give evidence.

Harrop told the court that after he had collected the Christmas Day collection 1i 1847, he took it to the vicarage, but he could not recollect whether anyone was in the room with the vicar. The next day, Sunday, December 26, I went to the vicarage to collect some papers for the choir. On being told the vicar was upstairs in the drawing-room, I went up, and the door was closed. I knocked and waited about a minute. There was no answer for that length of time, then the vicar called out, "come in," I walked in and found the vicar with Sarah Green; she was seated on the sofa. The vicar asked if I wanted the papers. I told him yes. He rang the bell and told Nancy Robinson, his servant, to fetch a book from the parlour. She returned a few minutes later and told the vicar she could not find the book. I collected the papers and left the room. Harrop told the court he had seen Mary Green at the vicarage five or six times. The vicar once told me to tell Mary Green he wanted to see her in the vestry. She remained in the vestry with the vicar for about six or seven minutes.

Mr Hudson, Mary Green's solicitor, asked Harrop what he thought when he found the vicar alone with Mary Green in the drawing-room and if he thought it was proper. No, I thought it was improper, replied Harrop. He said I am sixty-nine years old, and I have seen various Sunday School girls at the vicarage, besides Mary Green, he had known the vicar to send them on errands.

Mary Holgate, aged eighteen, was next called to the witness box. She told the court that she visited Mary Green around the time of Ebenezer Woodward's death. I opened the door, and after standing about for a minute or two and hearing no sounds, I saw the vicar in the kitchen. He had his back to me; from the motion of his arms, he seemed to be doing something with his dress. Mary came out of the kitchen into the front room, and the vicar stooped down near the edge of the slopstone, and when he walked out of the kitchen, he had two potatoes in his hand. Holgate corroborated Green's testimony fully as to what passed subsequently. I thought nothing about it until May when rumours about Mary's pregnancy broke out in the village.

Ann Ogden, aged twenty-one, was the next witness to be called. She told the court that she had gone with several other girls to practice singing at the vicarage on Monday evening. On leaving, Mary Green, Mary Swan, and several other girls walked down the hallway to the vicarage door. The vicar put his hand indecently on me and said, "Mary." I said, "No." The vicar said, "Who are you? I replied, "Me, sir." He said, "Good night, and make haste home." Mary Green, Mary Swan, and other girls were already outside the vicarage, about two yards from the door, and Green and Swan were laughing because the vicar had mistaken me for Mary Green. Ogden was then cross-examined at some length and explained that it was dark in the lobby; there were no candles lit, and at first, Mary Green had been at the back of the group of girls, but she pushed past everyone to get out of the vicarage, so I became the last of the girls to get to the door. I supposed Green and Swan were laughing because the vicar had mistaken me for her and had heard what he said to me.

Dr Frederick Tinker from Mottram proved that the birth of the child on the morning of Tuesday, November 30, agreed with the dates given by Mary Green.

Seddon's barrister then addressed the court for a considerable length of time. He said that according to Green's statement, Mr Seddon did not seek her out because Mrs Seddon asked her to fetch the magazines. He said that all the probabilities were against the truth of the story. It was not unusual for a Sunday School scholar to go to the vicar's study or drawing-room to have her name written in her Bible.

The appeal of the Reverand David Seddon, vicar of Mottram, against a bastardy order came up at Knutsford general quarter sessions on Friday, April 14 1848.

An ecclesiastical commission investigating the case for two days at Mottram concluded that "the charge was without foundation."

Mr Leigh Trafford and Mr Townsend - instructed by Mr Streeter, Solicitor, Manchester, counsel for the appellant; and Mr M'Intyre instructed Mr Hudson, Solicitor, Stockport, conducted the case for the respondent.

Mr M'Intyre, for the defence, opened his cross-examination as follows:- Are you a drawing frame tenter in the card rood at Broadbottom. Mary:- Yes, sir. At whose factory? Mary:- Mr Joe Sidebotham's. Are you a single woman? Mary:- Yes, sir. How old are you? Mary:- I was 21 on February 10 1848. Have you a child? Mary:- Yes, sir. A male or female? Mary:- A male. When was it born? Mary:- On November 30 1847. What surgeon attended you in your confinement? Mary:- Mr Fred Tinker, of Hyde. Who is the father of the child? Mary:- Mr David Seddon, the vicar of Mottram.

When Mary's testimony was complete, the cross-examination of other witnesses began. The testimonies were basically the same as those given at the Hyde Petty Sessions on Monday, January 10, and to the ecclesiastical commission at Mottram on 15 and 16 June 1847.

Mr Trafford began his cross-examination of Mary Green with the central questions: how long had she known Thomas Jackson, and how many times had she had intercourse with him during their relationship? Mary's relationship with Jackson and the number of times they had intercourse had nothing to do with the case; it was to discredit and blacken Mary's character by proving she was morally corrupt and no better than a prostitute. Seddon was a man of the cloth, and his accuser an unwed mother from the bottom rung of the social ladder. If Victorian England was lax in the matter of fair trials, it nonetheless had strict parameters for feminine behaviour. The purpose of sex was for reproduction only. Anything else was "morally wrong."

Mary told the court that she had kept company with Jackson for about three or four years. Trafford:- Did you have connections (intercourse) with him? Mary:- That's nothing to do with it. Trafford:- Do you mean you only had connections once? Mary:- I won't swear how many times he had intercourse with me. Trafford:- Was it not for two or three years running?

Mary:- We went out together for that length of time. Trafford:- Well, did he not have connections with you during that time; did he not have relations with you frequently during those three or four years? Mary:- I shall say nothing about it because it has nothing to do with this case.

Trafford:- Had he connections with you more than once, you are a Sunday School monitor, you have a bible in your hand, and you are bound to tell the truth. (Another pause) The Chairman:- Had he connections with you more than once? Mary:- He had intercourse with me once. The Chairman said:- This kind of evasive answer is called prevarication, and for this, you can go to prison, you should answer the question boldly at once, you have called God to witness that you are telling the truth, and the whole truth and you are bound to answer the question. Mary:- Well, he had, but I cannot see that that that has anything to do with the case at all. The Chairman:- You know it is going character and credibility. Trafford:- What age were you when you first had intercourse with Jackson? Mary:- I can't tell; there is no use in swearing. I can't say if I was more than fourteen. Trafford:- Will you say you were more than fifteen? Mary:- I don't know exactly. Trafford: Will you swear that Jackson was the first person you had anything to do with in that way?

Trafford had intimidated a vulnerable uneducated mill girl for almost two hours with sarcasm, hostile questioning, and attacks (as we have seen) on her character. It was a preview of how he would treat all the following hostile witnesses.

Surgeon Fred Tinker from Hyde testified he had attended Mary Green during her confinement. On hearing her account of intercourse with the Reverend David Seddon on March 16. He believed that Mary's child may have resulted from that connection.

The next witness brought to the stand was Ralph Sidebottom, a surgeon from Mottram. He stated that the Ecclesiastical Commission had questioned on behalf of Mr Seddon at Mottram. On January 7, Mr Street asked me to call round at the vicarage; Mr Seddon, Mr Street, and I believe Miss Cooper were present. They had sent for me to ask if I could tell them what had taken place at the meeting of the Ecclesiastical Commission I attended in Mottram, as Mr Street had sent for me only for that purpose. I told Mr Street I only knew one thing:- I believed Jackson's involvement in the affair had not been made clear. Mr Street said that he thought they had gone far enough with Jackson's involvement, as it would not do Mr Seddon's case any good. He did not believe it was proper to go any further. Mr Street then handed me a subpoena to attend the magistrates' court. Mr Seddon came into the room and was very agitated and excited. He sat on the table, stretched out his hand, and said, "Mr Sidebottom, there is just god in heaven who will visit you and your family if you don't declare about it." He then left the table and leaned on the mantle piece. He then said:- "This is a life and death case for me as a clergyman, but for you, as a medical man, it will do you no harm." I walked across to him; I was most excited at that point and asked:- "What do you mean by that?" I turned to Mr Street and asked him the same. He appeared as though he wanted the whole matter dropped.

Mr Seddon accused me of knowing much more about the affair than I chose to tell them. He then said:- "You have five sons, and that he had heard that one of my sons was in the habit of going to Mary Green's home.

That finished the respondents' case, and the court adjourned shortly before six o'clock until 8 45 the following morning.

The court reconvened at 8 45 the following morning.

Trafford addressed the court at some length. His address was rambling and disconnected. He said:- "The only essential witnesses in the case were Mary Green, Ellen Holgate, and Ann Ogden, and from the manner and demeanour in which the latter two girls give their evidence, it was pretty clear Mary Green had schooled them. Both did not come out well under Trafford's hostile questioning. He said the court should not believe the evidence of Holgate, for it was clear that if Seddon was in Green's house taking liberties with her when Holgate came into the house, he could have left by the back door. But according to Holgate, she entered the house by the front door and at first, neither Green nor Seddon knew she was there. Both were in the kitchen, and Seddon had his back to Holgate. All the witnesses for Green and Seddon were neither sure nor certain about the times and days when particular events occurred. On the other hand, even under four hours of hostile questioning by Trafford, Mary Green never changed her story.

M'Intyre replied at great length upon the whole case. He argued that the case put forward on the part of the respondent was entirely unaltered by the other side's witnesses. He felt confident the court would weigh both sides of the evidence and conclude that justice was required. After his summing-up, there was a loud burst of applause.

At half-past five o'clock, the magistrates retired to consider the evidence, and twenty-five minutes later, the Chairman quashed the order.

Mr Street moved that the appellant be allowed cost.

The Chairman replied:- "Oh no, we cannot give cost."

Mary Green had very little chance of getting redress against the Reverend David Seddon. The total weight of the establishment was against her, and the bench was the tool of the establishment. The magistrates presiding over the adjudication were Trafford Trafford, Esq., (Chairman), Edwin Corbett, Esq., Edward Jeremiah Lloyd, Esq., Joshua Bruckshsaw, Esq., and the Reverend William Brownlow. All were wealthy landowners, more likely to come down in favour of a man of the cloth than a poor factory girl. Moreover, Brownlow's selection to the bench violated the principle of impartiality. He should not have even been on the bench because he was a clergyman, as was Seddon.

The humiliation strategy used by Trafford, and upheld by the Chairman of the magistrates, were fundamentally inconsistent with a fair hearing. Trafford's tactic of badgering Mary Green about her previous sexual history was a ploy to undermine her credibility to cast doubt on her story.

If Seddon was not the father of Mary's child, what could she possibly have hoped to gain by blaming him? She had no ill feelings towards him, and there is no evidence of blackmail.

It makes more sense to assume that Seddon was a sexual predator who liked being around teenage girls. Undoubtedly, on the night of the choir practice, he sought out Mary Green in the hallway, but because the light was poor, he mistook Mary Swann for her. Mary, who had been at the back, pushed her way passed the other girls down the hallway to avoid contact with him. When Mrs Seddon sent her from the Sunday School to the vicarage to collect some magazines, little did Mary know she was walking into the lion's den. Once he got her into the drawing-room, Seddon closed the door and seduced her. After this, Seddon was sure Mary would keep her mouth shut, and even if she did tell someone, he only had to deny it. His word as a man of the cloth was worth more than that of a lower-class mill girl. However, there was very little chance of the court ruling in favour of Mary.

That is, however, far from the end of the story. Since I concluded my article, I have unearthed new evidence regarding the Reverend David Seddon. With the kind assistance of the St Kilda Historical Society, I can now prove that Seddon, while masquerading as a man of God, was an opportunistic sexual predator.

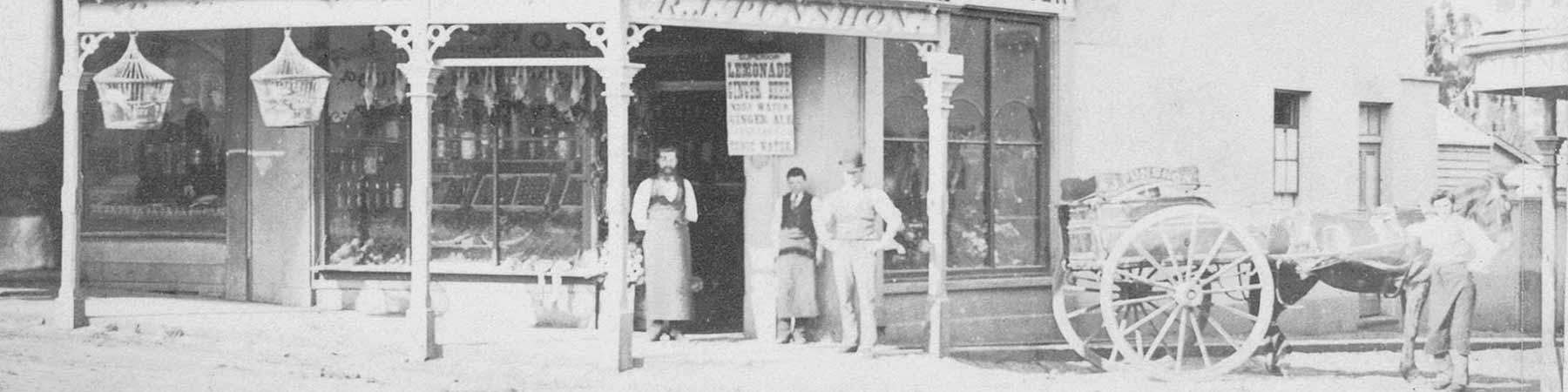

The Reverend David Seddon and his family arrived in Melbourne on December 16 1852, on board the ship "Bombay." In 1853 he was given the curacy of Christ Church, St Kilda. His wife Hannah died at the parsonage on July 21 1861, aged 48. He suddenly resigned his curacy on August 6 1868; he offered no reason for his resignation. He sailed from Melbourne for England on August 27 1868, aboard the "Kent," his furniture and other household belongings were auctioned off the following day.

In September, a local newspaper printed an article regarding rumours of immoral behaviour by two members of the clergy, the Reverend David Seddon and the Reverend Joseph Beer; Seddon was believed to have committed inappropriate offences against female inmates of a blind asylum. The newspaper did not go into the sordid details. In October 1868, the Melbourne newspaper the "Argus" reported that Seddon had fled St Kilda in "consequence of accusations he could not refute, of having been guilty of serious improprieties." All in St Kilda took the view he had fled the colony in a hurry and must have been guilty as per rumours.

The following is an extract from an article entitled "Clerical Scandals" published in another Melbourne newspaper on October 12 1868.

"The public has been distressingly agitated by rumour affecting the character of two local clergymen, the Reverend David Seddon and the Reverend Joseph Beer. Some rumours have been false, but some are true. The fact the Reverend Seddon of the Church of England and the Reverend Joseph Beer of the Independent church have left the colony may be accepted as proof that the charges brought against them were irrefutable to their continuance in ministerial office."

David Seddon married Elizabeth Willam, the widow of George Willam, on November 4 1869. During the same month, he was appointed pastor of Tything district Church and commenced his duties on Sunday, November 28 1869. Seddon completed his term at Tything on September 28 1872. After the death of his second wife, he married Emily Richards in 1877; he died on March 7 1893. He left £984 16s to his widow.

The following is an extract from a local newspaper published on Saturday January 8 1882. At the annual Christmas party of the Broadbottom Primitives held on Saturday, December 31 1881, Mr A K Sidebottom had this to say about two of the Vickers of Mottram that he had known. "The first vicar was Mr Johnson, a fine venerable gentleman; he was an excellent preacher. The next vicar was David Seddon; he had been a missionary in Jamaica, and all the company present know why he had to leave."