This article, by Peter Pereyra, focuses on William Arnott, St Kilda's first circulating librarian, where he maintained his business at three different locations in High Street.

‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡

Circulating libraries operated in Melbourne from the 1840s until the mid- to late 1970s.[1] From about 1930, the libraries steadily increased in number—peaking at over four hundred in 1940[2]—and spread rapidly throughout the suburban area until they began to slowly decline from the late 1950s. During this time the libraries loaned a vast number of books to the majority of the populace who could either not afford to purchase them or preferred to read books rather than own them. Moreover, for the much larger part of the existence of the circulating libraries there was a prolonged lethargy, and occasional opposition by councils to establish rate supported libraries, as seems to be the case in the St Kilda municipality, which sustained the viability of the circulating library trade. For the purposes of this article, the term circulating library refers to a privately-owned business that loaned books to patrons on the basis of a periodic subscription until about 1930 when, almost without exception, the libraries levied a set fee-per-book, usually for a seven-day period. The libraries were either stand-alone, that is, the sole or primary trade of the premises, or adjuncts to other businesses, predominantly, and initially, booksellers and from about the mid-1930s, newsagencies. During the nineteenth century, the circulating library numbers in Melbourne and its suburbs were relatively low, sporadically rising and falling and only occasionally reaching double-figures.

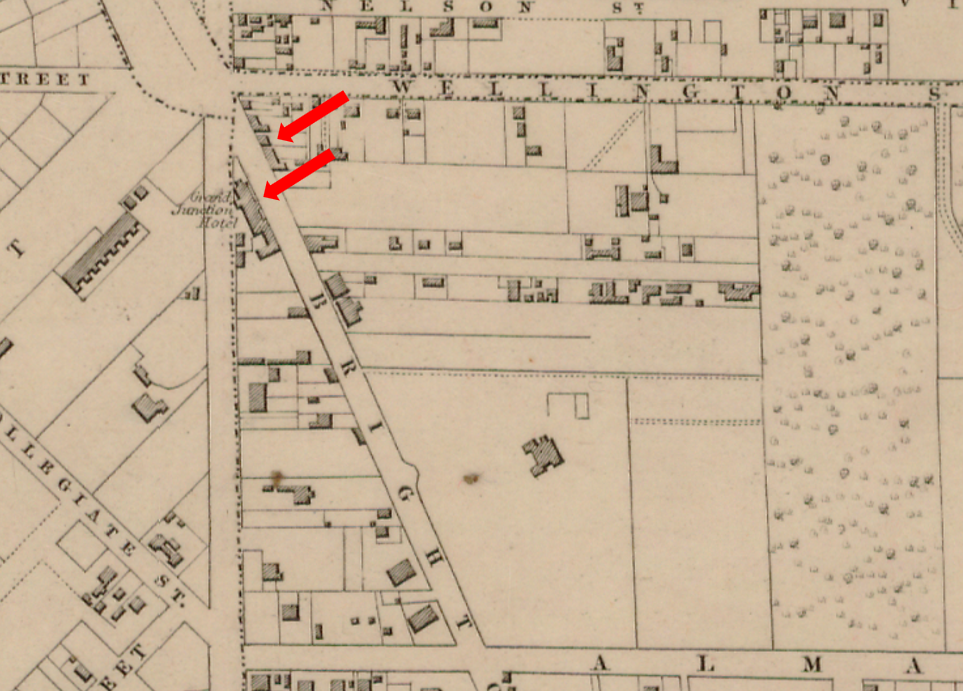

This article focuses on William Arnott, the first bookseller and the first circulating librarian to establish in St Kilda. I have been unable to find any information about Arnott, who was born in or about 1820, other than that associated with his business and that, too, is scarce. However, Arnott obviously had considerable acumen as a bookseller and librarian that allowed him to maintain his business at three different locations in High Street (now known as St Kilda Road) for thirty-three years, a period of longevity which very few St Kilda booksellers or circulating librarians would equal.[3]

The primary source of identification of Melbourne’s booksellers and circulating libraries is the Directory of Victoria, (hereafter “Directory”) published yearly from 1857 until 1974.[4] The Directories are generally reliable, but the annual data collection methodology, and the collation and editing of the increasingly voluminous publications led to some omissions and inaccuracies that quite often cannot be resolved. Several such issues arise in this study for which only limited clarification can be offered. Newspaper articles and advertisements are a useful, and more contemporaneous, resource that offer details otherwise missing from the meagre annual Directory listings. Remnant books from a significant number of Melbourne’s libraries from the more dynamic period, that is, from about 1920 to the late 1970s, are retained in many historical collections and these provide invaluable information about the operations of the libraries. Regrettably, few exemplars from Melbourne’s nineteenth-century libraries are extant for examination.

‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡

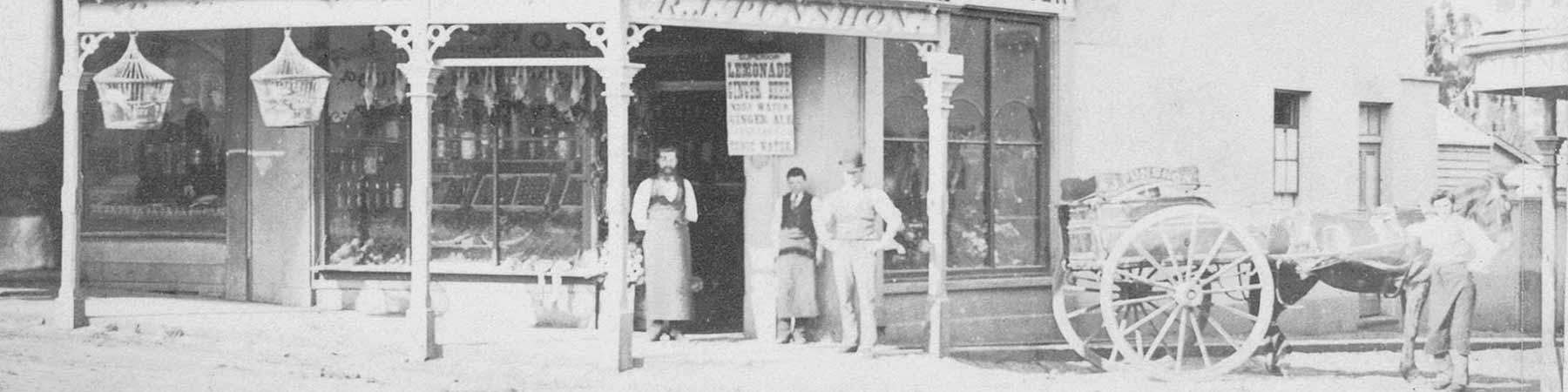

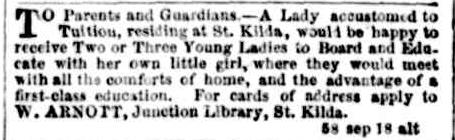

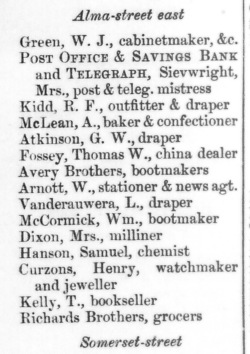

The Directories began publication in 1857 but the suburb of St Kilda was not included until 1859. William Arnott is listed in the 1859 Directory as a “Bookseller and stationer. Post office,” at 5 High Street, St Kilda, but he had established his business at a considerably earlier time. A newspaper advertisement in 1854 provides a contact address of “W. Arnott, Junction Library, St Kilda.”

Advertisement from The Argus, 15 September 1854, p. 8.

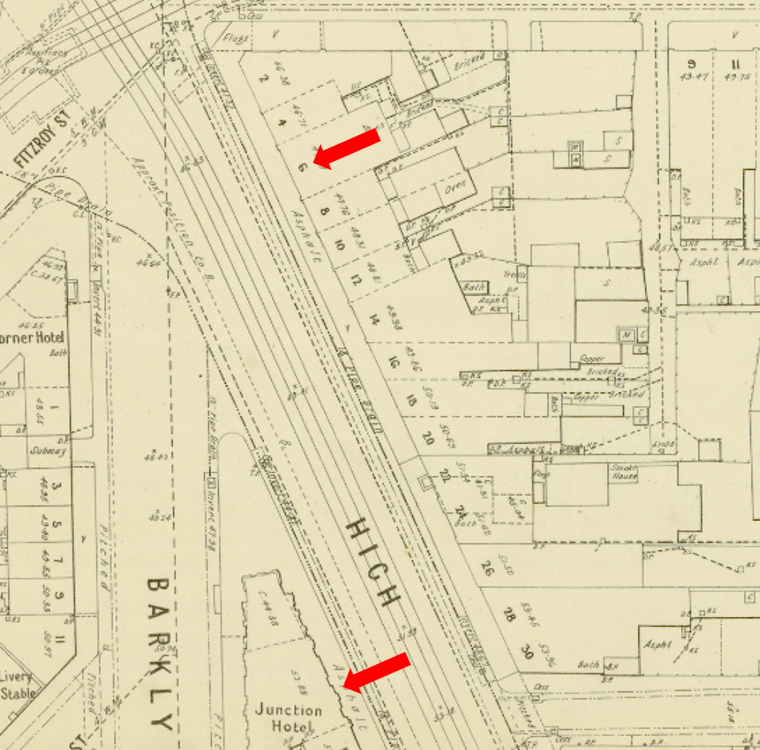

A further advertisement appearing in 1855, “Mr. William Arnott, bookseller, opposite the Junction Hotel, St Kilda…”[5] suggests that Arnott’s premises were on the east side of High Street, somewhere between Wellington and Octavia Streets. It is reasonable to assume that Arnott remained at this location until the time of his first listing in the Directory, at 5 High Street, which was the third premises south of Wellington Street. His claim to be “opposite the Junction Hotel” was slightly misleading, but as the hotel was probably well-known, it would have provided a reasonably reliable datum for clients to find his shop. The location of the premises can be seen, in its context—but without a realistic perspective due to the scale of the map—with the Junction Hotel, on the Kearney map of 1855,[6] which was prepared during the time that Arnott occupied the building.

Section of the Kearney map of 1855. Arrows identify the hotel and the building occupied by Arnott, 1854–1860.

Section of the Kearney map of 1855. Arrows identify the hotel and the building occupied by Arnott, 1854–1860.

A more accurate depiction of Arnott’s building in relation to the Junction Hotel (demolished in 1973 as part of the road-widening of High Street), can be seen in the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (“M&MBW”) plan of 1898, also marked with arrows. This plan, prepared at a much greater and more accurate scale, also displays the establishment of buildings on all of the allotments of High Street which was obviously developing as a commercial hub of the suburb.

M&MBW detail plan 1358, City of St Kilda, 1898.[7]

M&MBW detail plan 1358, City of St Kilda, 1898.[7]

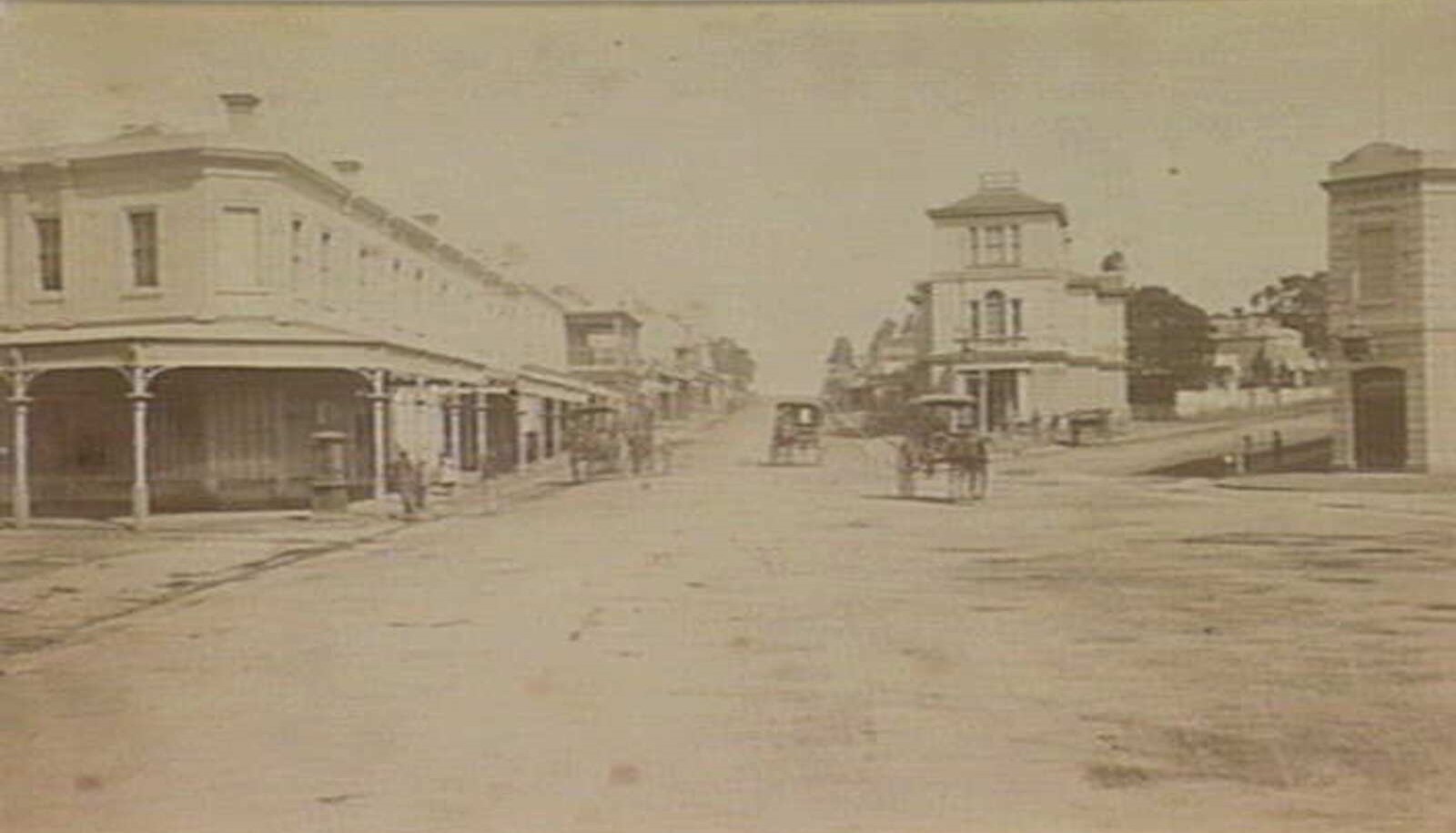

A photograph of the St Kilda junction, although dating from at least fifteen years after Arnott had vacated the premises, probably depicts the substantial masonry buildings that were in existence at the time of his occupancy. Arnott’s premises are shown in the left foreground.

St Kilda Junction, possibly from the 1870s, showing the façade of Arnott’s premises.[8]

St Kilda Junction, possibly from the 1870s, showing the façade of Arnott’s premises.[8]

Arnott advertised quite frequently while he occupied these premises, both as a bookseller and circulating librarian, stating his terms for the use of his library as “per month, 5s.; per quarter 12s.; per annum, 40s.”[9] This appears to be quite a reasonable subscription scale as, for instance, Thomas Buzzard, a prominent circulating librarian at 181 Bourke Street East, Melbourne, advertised his fees in the same year, 1856, as £1 for three months and £3 for twelve months.[10]

‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡

I have found no evidence of any other bookseller or circulating librarian operating in St Kilda from the time of the commencement of Arnott’s business until 1859, when George Slater commenced trading as a bookseller and circulating librarian at 93 High Street, St Kilda, also on the east side of the street, in the second premises south of Somerset Street.[11] Slater was only in operation for two years until 1861 and in the following year, Edward Esquilant established as a bookseller and circulating librarian at 89 High Street, on the northeast corner of Somerset Street. W. J. Wilson succeeded Esquilant in 1863 but ceased trading in 1864. For the following twenty years during which Arnott maintained his business in High Street, he had no competition to his circulating library business (except for Charles Thurston, from about 1884, see below), although about twelve booksellers operated in High Street (between the Junction and Carlisle Street) during that time, none of whom traded for more than eight years.

After five years of operation at his original site, in 1860, Arnott relocated his business to number 54 High Street, on the western side of the street. A larger analysis of the locations of Melbourne’s booksellers and circulating libraries over the period of the Directory’s publication reveals that a considerable number of proprietors moved premises, often several times, within the same street or near vicinity, probably to take the opportunity of a more advantageous shop rental or to establish in a more prominent position. It is doubtful that the premises at 5 High Street were not sufficiently prominent as it had several other occupants and then, in 1865, R. Woods commenced trading as a bookseller in the adjoining premises at 7 High Street. Woods was succeeded at 7 High Street by Joseph Fourdrinier, bookseller, who, in 1869, relocated to 5 High Street (Arnott’s original premises) and the shop was continually occupied by a number of people who traded as either a bookseller or stationer until about 1918.

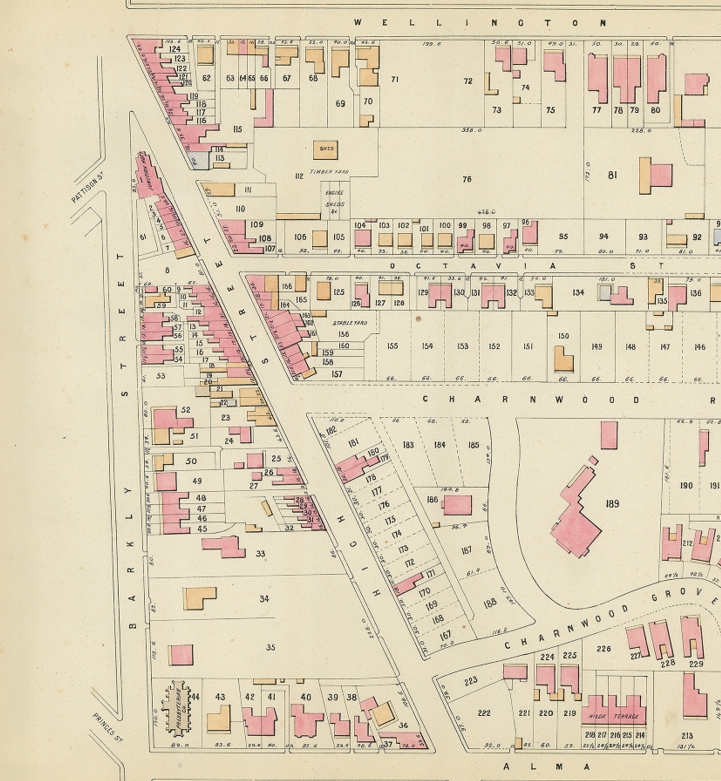

The precise location of Arnott’s premises at 54 High Street is difficult to determine. The 1860 Directory lists seventeen premises on this part of High Street between the Junction and Alma Road, including two entries of “vacant land.” The Junction Hotel is numbered as 2 and the next premises, occupied by Joseph Marsh, zinc worker, is at number 30, with the last premises on the block numbered as 86. Sheet NW1 of the Vardy map series of 1873,[12] reflecting the buildings and allotments about six years after Arnott vacated the premises, shows thirty-seven properties on this block, with three large properties appearing to be land at the rear of premises on Barkly Street. It seems likely that Arnott’s shop was among the cluster shown on the section of High Street between Octavia Street and Charnwood Road.

A section of Sheet NW1 of the Vardy map series showing buildings on the west side of High Street.

‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡

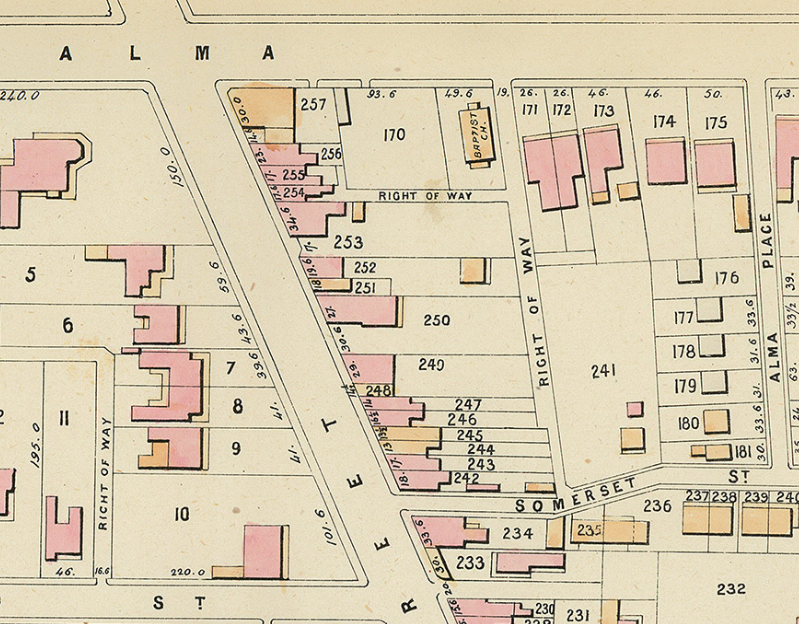

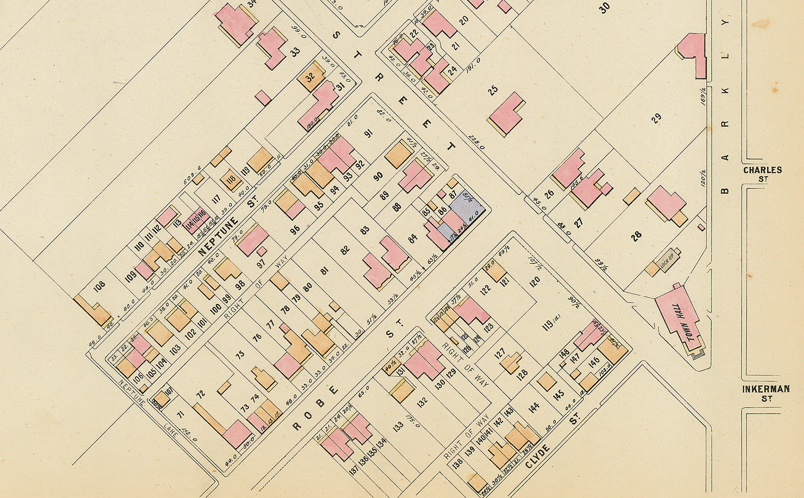

In 1867, Arnott vacated his shop on the west side and relocated again, for the last time, returning to the east side of High Street. The 1867 Directory lacks street numbers for premises, but he was situated in the middle of the block between Alma Road and Somerset Street. In 1867 and 1868, he is listed in the Directories as a bookseller, in 1869 as “stationer and postmaster: post office and savings bank,” but in 1870 as “stationer and newsagent.” According to the 1870 Directory, the post office and savings bank relocated five premises to the north of Arnott’s shop to a discrete premises managed by a postmistress. At this time, all of the allotments on this block appear to have buildings erected and a concordance of the Vardy Map and the 1873 Directory can be established, with Arnott’s premises identified as site “250” on the map, as shown, below.

Section of the Vardy Map Sheet NW5, above,the High Street listing of the 1873 Directory, p. 326, below.

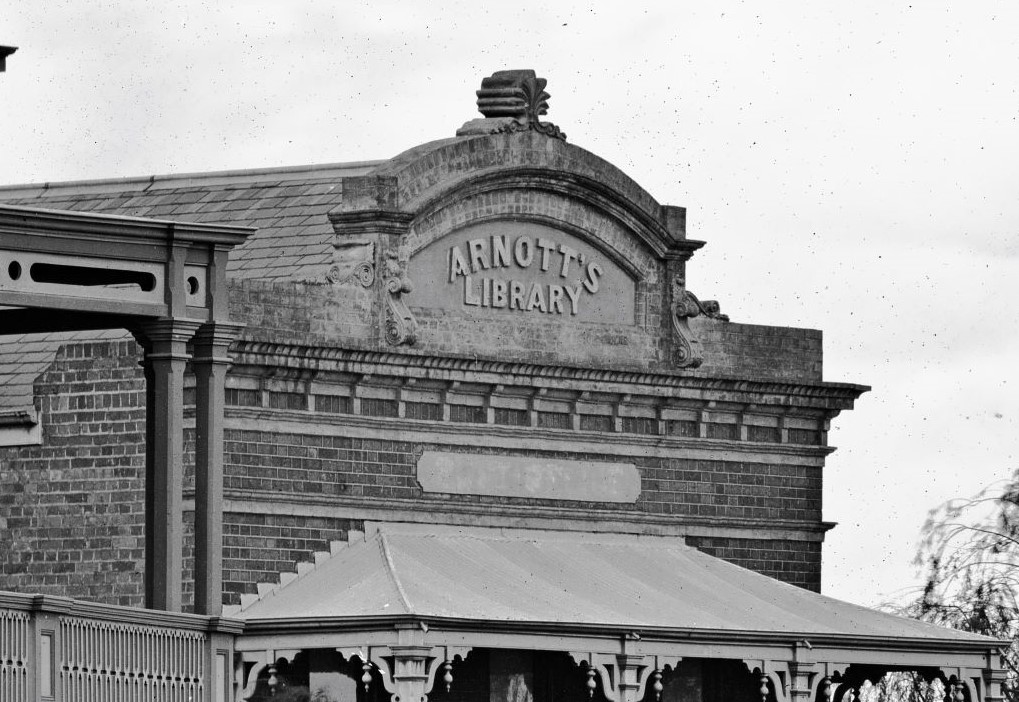

A photograph of High Street looking south from a position near Alma Road shows Arnott’s premises with the words “Arnott’s Library” in raised lettering on the parapet, and sign-written on the three panels of the front of the awning, “Bookseller. Arnott. Stationer.”

High Street, St Kilda, looking south from Alma Road.[13]

High Street, St Kilda, looking south from Alma Road.[13]

The catalogue record for the photograph provides a date of creation of 1870–1875, describing it as a “negative 10in. X 12.in. glass,” and when viewed from the website (for which the link is provided in the endnotes) displays at very high definition, so an extraordinary amount of detail can be discerned. As a result, much of the building signage can be compared to the street listings in the Directories, and using that information, a more accurate date for the creation of the photograph is possible. The post office, which can be seen in the left foreground, was established in this position in 1870—after Arnott relinquished the post office role—and remained at this location until 1876.[14] The next series of premises adjoining the post office were occupied by R. K. Kidd, outfitter and draper, Alex McLean, baker and confectioner, G. W. Atkinson, draper, Thomas Fossey, China dealer, Avery Brothers, bootmakers and then Arnott’s shop, and the signage for each business, except for that of Kidd, can be discerned. I have no information as to whether Arnott owned the premises he occupied, but he obviously employed an artisan to apply the raised lettering on the parapet of his shop, preferring “library” to either bookseller or stationer, the latter trades being those he elected to have listed in the Directories.[15] Similar raised lettering appears on the premises of Atkinson of which only the last two letters can be seen so it can only be speculated that the wording of this sign was “drapery”. Four premises south of Arnott’s shop, Lot 245 on the Vardy Map, the name “J. M. Thomas” appears on a building façade above the awning. Thomas appears in the Directory for a single year, 1874, (although his trade is not listed) but it seems that he acted quickly to engage a signwriter. This clearly suggests that that photograph cannot have been taken prior to 1874, but regrettably, defining the latest date on which the photograph might have been taken presents a difficulty. McLean relocated to premises on the northeast corner of Somerset Street in 1874 so, if it can be assumed that subsequent occupiers of shop—1875, George Hayward, confectioner or 1876, J. Prince, baker and confectioner[16]—were diligent in attending to sign writing, then this narrows the date of the photograph to 1874 or 1875, allowing for a maximum of one year between the Directory agents collecting occupant data and the publication of the next edition.

‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡

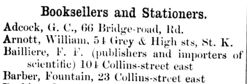

In 1872, Arnott opened a second bookselling business at 54 Grey Street, St Kilda, which appears to have survived for only a single year. He is listed in the 1872 Directory at both addresses, and one advertisement has been located, the advertiser using Arnott’s Grey Street address as a contact point.

Entry in 1872 Directory, p. 692,advertisement from The Argus, 16 February 1872, p. 1.

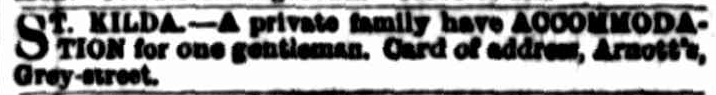

Although the Directory provides an address of 54 Grey Street in the “trade and profession” index (as shown, above), it does not list the numbers in the street listings, so it is difficult to determine the precise location of Arnott’s premises, but he was situated on the west side of Grey Street somewhere between Robe and Clyde Streets. It is apparent that many streets in St Kilda were renumbered in the early 1890s—including some alterations of the application of odd and even numbers to opposite sides of the street—and Grey Street was no exception, with the premises on the west side bearing even numbers until about 1892, after which, they were assigned odd numbers. Sheet WW4 of the Vardy Map Series, shown below, displays buildings on the block containing Arnott’s premises. However, the map does not show buildings on the section of Grey Street between Clyde and Barkly Streets, but the Directories, 1870–75, list four shops on that block and the Court House Hotel on the Barkly Street corner, which is either a curious omission from the map, or my misinterpretation of the map content. Several of the existing buildings between Robe and Clyde Streets appear to be of considerable age but it is unclear whether they were extant in 1872, when Arnott might have occupied one of them.

Section of Sheet WW4 of the Vardy Map Series.

Section of Sheet WW4 of the Vardy Map Series.

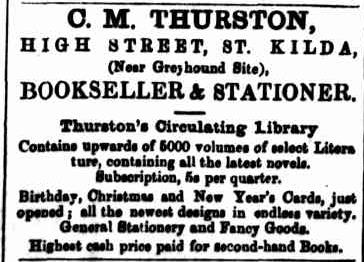

For the remainder of his occupancy of the premises in High Street, Arnott is listed in the Directories as “stationer and newsagent,” but frequent newspaper advertisements appear over the following years—predominantly providing his business as a contact address rather than for his own promotion of his stock—which variously describe his business as either a bookshop or library. In February 1882, Arnott announced that he was retiring and offered his “large stock at greatly reduced prices.”[17] Four months later he offered his library collection for sale, “Library of 1040 volumes, in fair condition, comprising most of the best authors, suitable for mechanics’ institute or country bookseller. Arnott, St. Kilda.”[18] When it is considered that in the 1930s and 1940s, the peak period of the operation of circulating libraries in Melbourne, a minimum viable lending collection might be estimated at fifteen hundred books, Arnott’s stock seems to be impressive for the time. However, for perspective, in 1887, Charles Thurston, a bookseller of High Street, St Kilda, who had maintained a circulating library since about 1884, advertised a significant circulating collection of 5,000 volumes, presumed to be in good condition, so Arnott’s books had obviously been frequently loaned but, perhaps, not expanded or refreshed as he contemplated retirement.

Advertisement for the circulating library of C. M. Thurston.[19]

Regardless of his stated intention to retire, Arnott continued to appear in the Directories, and infrequently in advertisements in the newspapers, until 1886, when he sold the business to W. J. Lormer. I have found no other references to Arnott, who seems to have entered retirement, until his death, aged 74, in 1894.[20]

W. J. Lormer continued to trade from the premises, listing in the Directories as a bookseller from 1887 until 1892, but also conducting a circulating library as, in his frequent newspaper advertisements, he announces his business as “Lormer’s Library, High Street, St. Kilda.”[21] In about 1893, Lormer relocated to Melbourne’s CBD, operating variously as a bookseller and circulating librarian from three different locations before apparently leaving the trade 1898.[22]

It is pleasing to find that the building occupied by Arnott from 1867 and later by his successor, Lormer, still survives. It appears to be the only building on the block—Alma Road to Somerset Street—which remains from the time that the photograph was taken in the mid-1870s, its parapet shape and upper-façade decoration making it easily identifiable. Although the raised lettering on the parapet has been removed, it seems that there might still be evidence of the occupancy of the booksellers and stationers, that is, Arnott or Lormer, on the building.

It seems that some refurbishment of the shop premises at the front of the building has exposed the area to which the awning, shown in the photograph of the 1870s, was attached.

Detail, from the previous image, of the façade of Arnott’s building.

Detail, from the previous image, of the façade of Arnott’s building.

Although far from clear, the panel above the present shop window appears to contain a word ending in the letters “…ioner,” as shown in the image detail, above. It seems reasonable to suggest that this word was “stationer”, and a part of a longer series of words, perhaps mirroring those that appeared on the front of Arnott’s awning in the 1870s. The sign might have been applied during Arnott’s occupancy or that of Lormer, who continued with the business. There is also a possibility, although less convincing, that the sign displayed the word “confectioner,” from the time when the premises were occupied by Mrs A. Hawkins (listed in the Directories as a confectioner), from about 1893 until 1900, after which she relocated to premises further south. I can find no other subsequent occupant of the building whose business type would suggest the application of such a sign.

‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡

Commencing his business at a time when there were few bookshops or circulating libraries in Melbourne’s suburbs, William Arnott was a forerunner of his trades and clearly successful. He would have been aware of other booksellers establishing, not only in High Street, but in Barkly, Grey, Camden, Chapel and Wellington Streets, and observed all closing after relatively short periods of business. Moreover, after a very short period of competition in the early 1860s, he held the monopoly of the circulating library trade in High Street for almost twenty years. After his pioneering business efforts, a considerable number of bookshops continued to be launched in the St Kilda and Elwood areas, with varied success, and from the late 1920s, circulating libraries became so popular in the municipality that by 1940 the residents supported more libraries than any other of Melbourne’s suburbs.

Endnotes

[1] There are more than one hundred and twenty circulating libraries listed in the last edition of the Directory of Victoria in 1974, but analysis shows that many of those listed were book exchange operations. From the evidence that I have discovered, the latest a book was loaned was a volume from the Bentleigh Book Club, 398 Centre Road, Bentleigh. The book, Denzil Batchelor’s The Taste of Blood, Melbourne, William Heinemann Ltd, 1956, contains three borrower date stamps from 1980 on the rear fly leaf of the book, the last being 8 May 1980. The book is held in the Monash University Rare Books collection. However, without further details about the actual operation of the library, its closure date cannot be determined, so it is equally likely that the Duchey Library of 3 Ormond Road, Elwood, might have continued into the 1980s. A volume from the Duchey Library, Diana Raymond’s Between the Stirrup and the Ground, London, Cassell and Company Ltd., 1956, in the Monash University Rare Books collection, contains library stamps on the inside rear cover to June 1978.

[2] This number is derived from the “trade and profession” listings in the 1940 Directory (see fn 4, below), but is most likely to have been appreciably higher, by as much as fifty per cent, if libraries that were adjuncts to other businesses, especially newsagents by this time, were able to be accurately identified.

[3] As a sole trader, Arnott, operating from three different premises for thirty-three years, was only surpassed in longevity in the St Kilda and Elwood suburbs by booksellers, Miss Catherine Lawson, 52 Robe Street, St Kilda, 1883–1923, Miss E. Swanell, 102 and 106 Carlisle Street, St Kilda, 1924–1962, and circulating librarian, Mrs E. Cherry, 229a Barkly Street, St Kilda, 1940–1974. The Thurston family, mentioned later in the narrative, conducted a bookselling and circulating library business for seventy-one years, but this appears to have been under the management of three separate people.

[4] Sands and Kenny, Directory of Victoria, Melbourne, Sands & Kenny Pty Ltd, 1857–1861 and Sands and McDougall, Directory of Victoria, Melbourne, Sands & McDougall Pty Ltd, 1862–1974. The Directories contained, amongst other information, an alphabetical list of the names of all building occupiers of the suburbs covered (which continually increased as Greater Melbourne expanded), a section containing an alphabetical list of all of the suburbs listing of the occupiers of each street, also arranged alphabetically, in each suburb, and a trade and professional section that forms an alphabetical index of vocations.

[5] The Argus, 30 June 1855, p. 1.

[6] James Kearney (complier), Melbourne and its Suburbs, 1855, published by Andrew Clarke, Surveyor General. One map on four sheets of which sheet four displays St Kilda, at a scale of 1:10,000. From the collection of the State Library Victoria, http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/89107

[7] M&MBW plan from the collection of the State Library Victoria. http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/122379. This plan is to a scale of 1:1,920, or 160 feet to 1 inch, which provides a more realistic perspective.

[8] Photograph of the St Kilda Junction dated “ca. 187?” From the collection of the State Library Victoria. http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/4252650. A much clearer image of the Junction can be found at http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/107130, also in the State Library Victoria collection, but which does not provide the same perspective, that is, it does not show the façades of the shops on the east side of High Street.

[9] The Argus, 10 January 1856, p. 7.

[10] The Argus, 19 June 1856, p. 8.

[11] Slater was operating as a bookseller in High Street, St Kilda from at least June 1858 as he appears in a newspaper advertisement at that time providing his details as a contact point, “Mr. Slater, bookseller, St Kilda,” The Argus, 21 June 1858, p. 8. Slater’s experience in the bookselling trade and operation of circulating libraries pre-date Arnott as Slater appears to have operated the first circulating library outside the City of Melbourne. In July 1853, Slater established as a wholesale bookseller at “13 Wellington Street, near Black’s, Collingwood,” The Argus, 25 July 1853, p. 7, and in August and September 1853 he placed numerous advertisements in the newspapers for his Wellington Library, operating from the same address.

[12] J. E. S. Vardy, Plan of the Borough of St Kilda, published by Hamel and Ferguson, 85 Queen Street, Melbourne, 1873, Sheet NW 1, from the St Kilda Historical Society website. I am grateful to my State Library User Organisations’ Council colleague, Peter Johnson, for bringing this invaluable map series to my attention.

[13] From the collection of the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, at https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/nZNmjG8n. A second, stereoscopic image taken from approximately the same street position, possibly shortly after the first image was exposed, can be found at https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/n7o74Ldn#viewer This latter image provides a clearer view of the post office in the left foreground.

[14] According to the 1877 Directory, the post office relocated to the north-east corner of Inkerman Street—the position currently occupied by the Post Office Club Hotel—before again relocating to the south-east corner of High Street and Inkerman Street, where the post office building, clearly marked, is still extant.

[15] Although Arnott appears to have maintained a circulating library during the entire period of the conduct of his business in High Street, he is listed variously as bookseller, stationer, and newsagent in each year and as a circulating librarian only from 1863 to 1877.

[16] Alex McLean had been in occupancy of the premises since 1869 and it is possible that the fittings and equipment for the manufacture of confectionery and bakery goods remained in the shop, which attracted the subsequent occupiers who continued with these trades.

[17] The Argus, 16 February 1882, p. 5.

[18] The Argus, 28 June 1882, p. 1.

[19] The Telegraph, St Kilda, Prahran and South Yarra Guardian (Vic.), 3 December 1887, p. 4. C. M. (Charles) Thurston is first recorded in the Directories as a bookseller in 1885 in High Street, St Kilda. No street number is listed but his premises were on the south-west corner of Vale Street. From 1890 the street address of 391 is listed and from 1896, the street address of 389 is provided as the street listings in the Directory reveal his relocation to the north-west corner of Vale Street. The Directories list C. M. Thurston, 1885–87, Miss Thurston, 1888–89, C. M. Thurston, 1890–97, Mrs G. Thurston, 1898–1932, and Miss C. Thurston, 1933–55, a remarkable seventy-one years of operation by the same family.

[20] Arnott’s death was announced in The Australasian, 29 December 1894, p. 45, “Arnott—On the 21st inst., at Fonthill, The Avenue, East Malvern, William Arnott, late of St Kilda, in his 75th year.”

[21] See, for instance, The Age, 28 March 1887, p. 1, The Argus, 19 October 1888, p. 1, and The Age, 8 March 1892, p. 7.

[22] It might be conjectured that Lormer had little experience or knowledge of the book or library trades when he purchased the business from Arnott. A newspaper article reports that, on purchasing the business he “learnt to his surprise that he had as a competitor what was known as the Free Public Library of St. Kilda from which books were lent out, not free, but by payment of a quarterly or annual subscription.” Lormer protested that “the Free Library in letting out books and making a charge for same was a departure from what was originally intended, and an unfair competition with those in business in the district,” The Telegraph, St Kilda, Prahran and South Yarra Guardian (Vic.), 31 July 1886, p. 7.